Other Sand Stories

Master of Architecture Thesis

Advisors Marcel Sanchez and Neyran Turan / UC Berkeley, Spring 2021

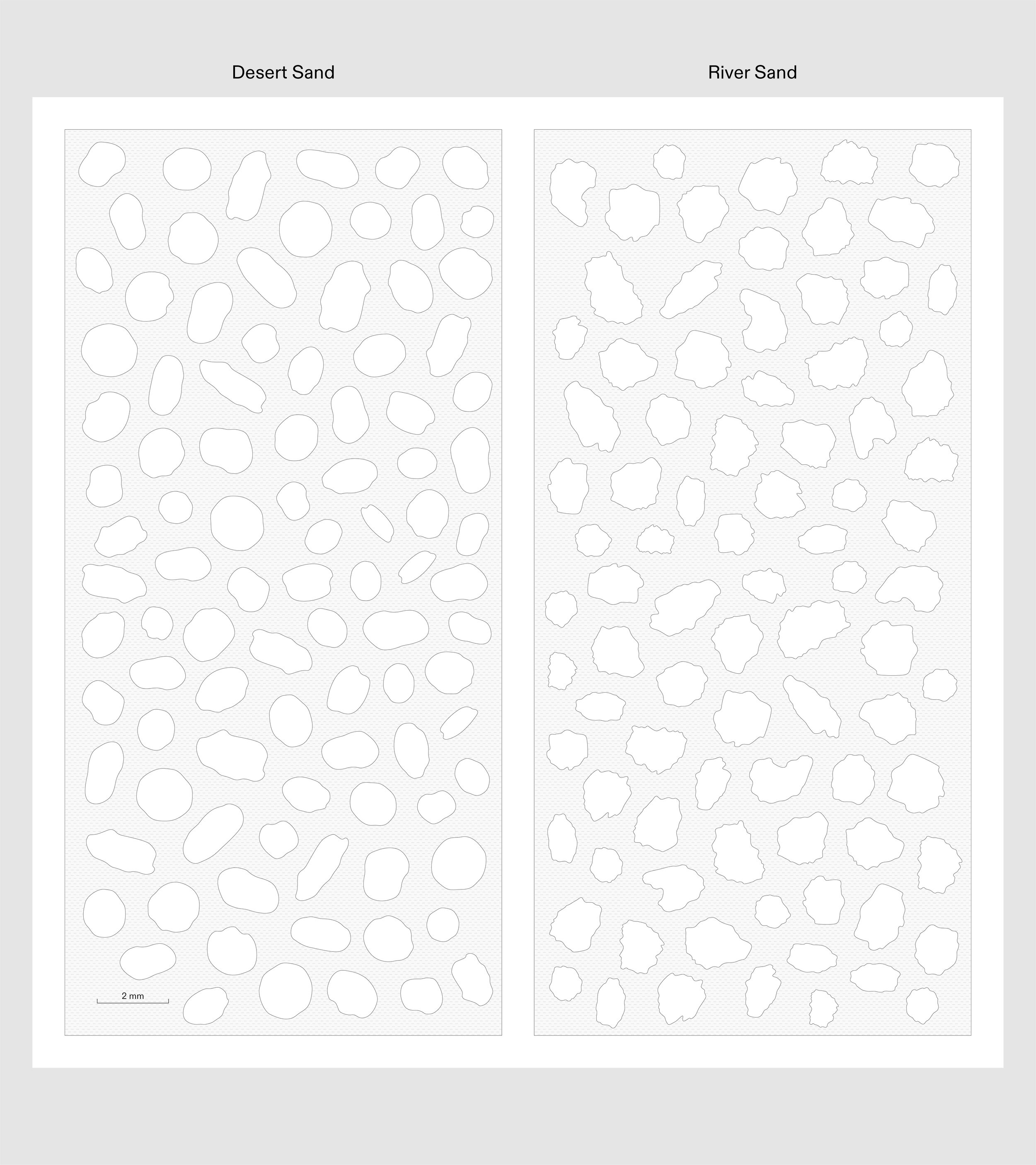

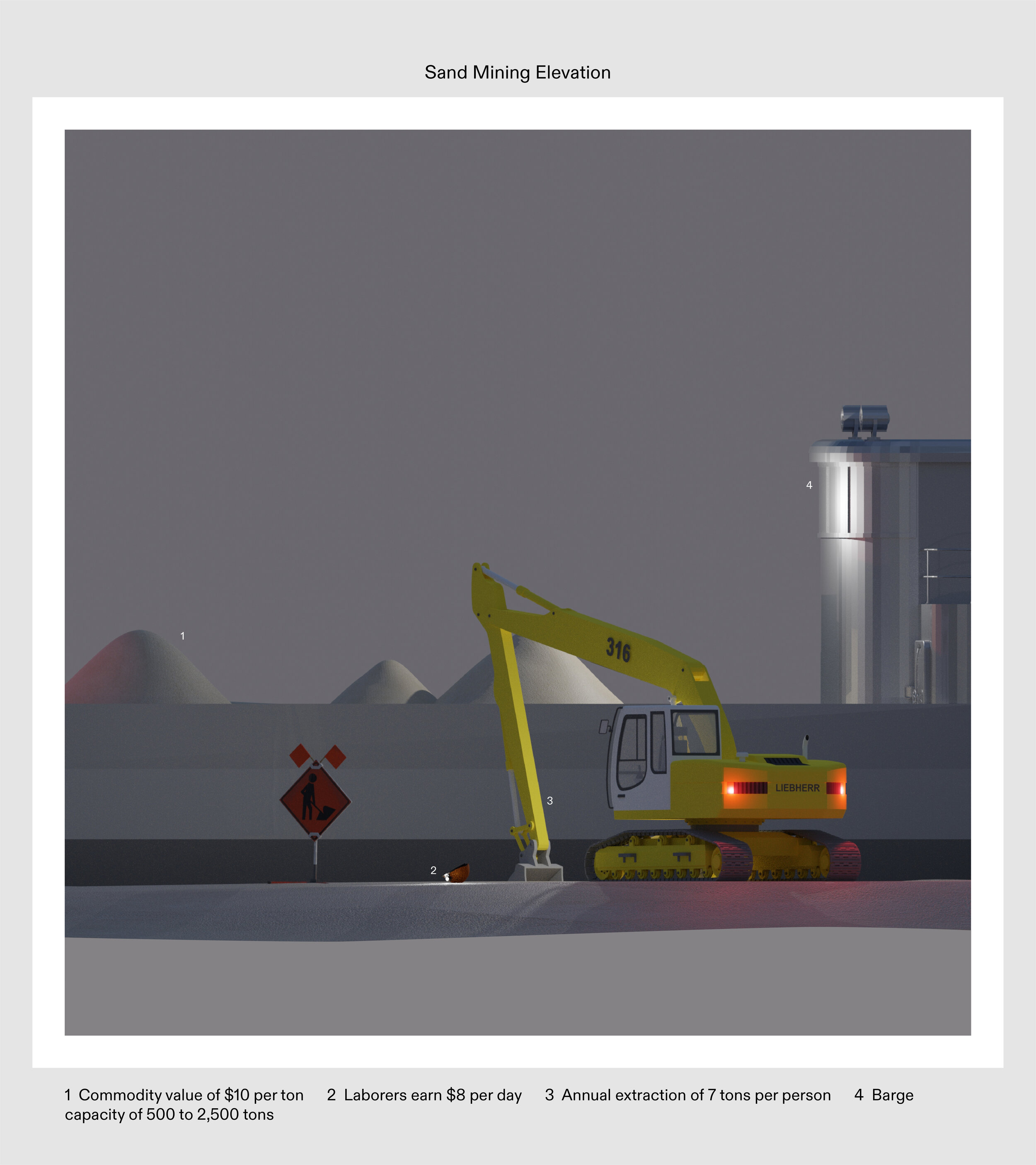

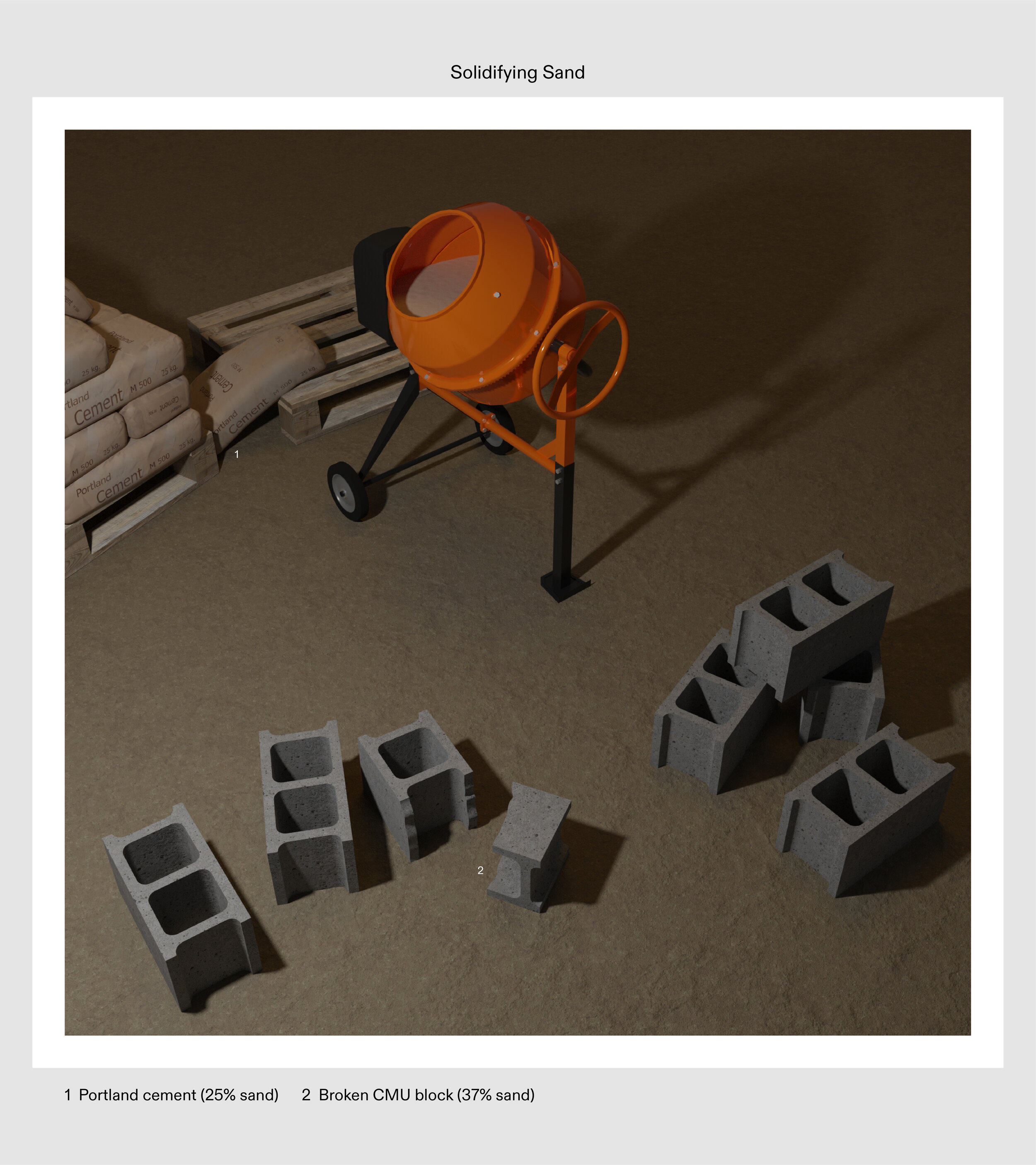

Sand is the second most consumed natural resource in the world, contributing to the production of glass, concrete, golf courses, paint, bricks and land to name a few. But sand is not as abundant as it seems—desert sand is too rounded from wind erosion to stick together for use in concrete or other construction materials.

River and coastal sand is thus what feeds the planet’s largest extractive industry, which depletes the finite resource at about two times the rate it can be replenished from upstream.

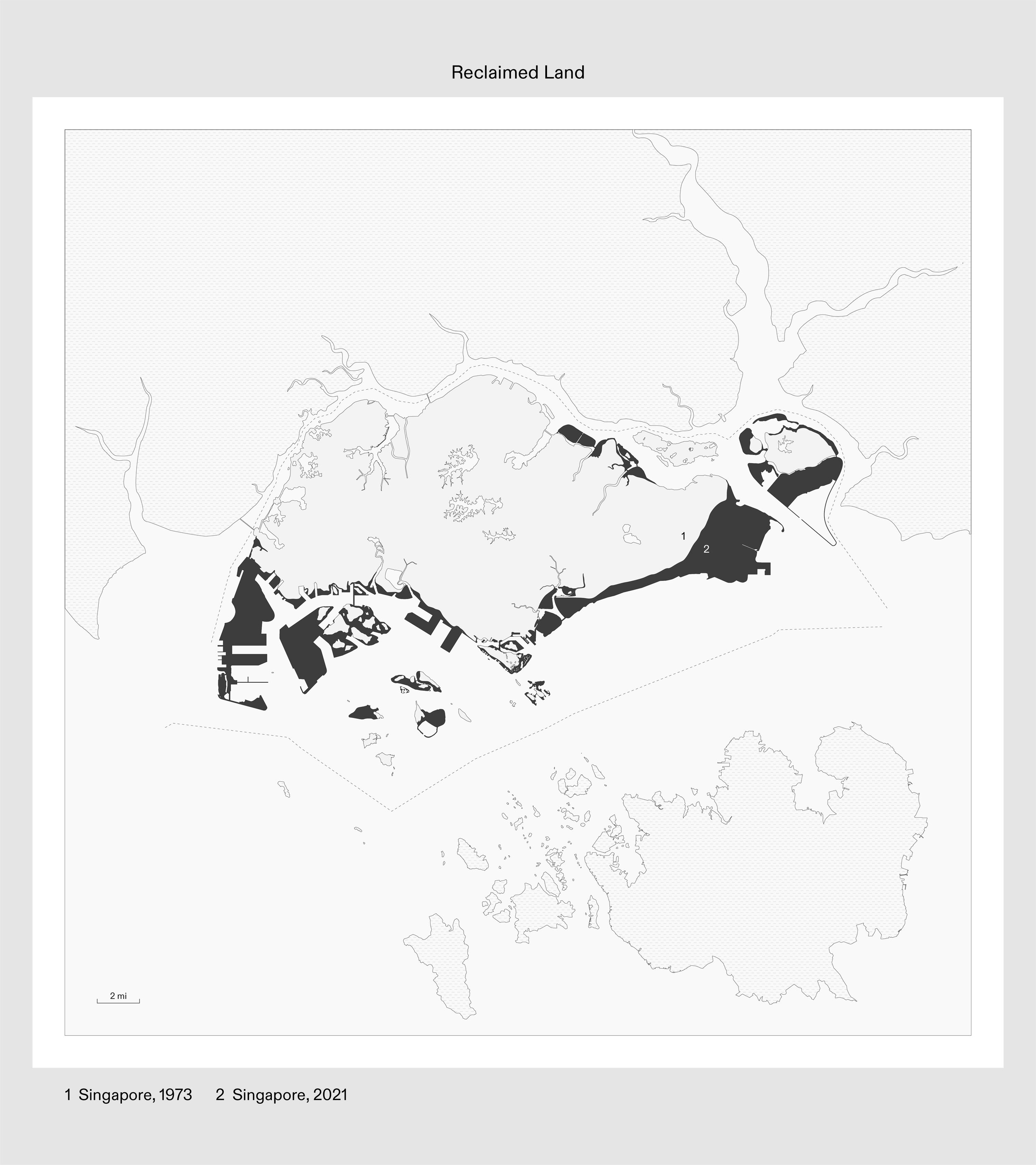

Singapore has imported sand from other countries, legally and illegally, effectively increasing its land area by over 25% in the last several decades—an accumulation of about 140 square kilometers of new territory, mainly grounding industrial and luxury real estate developments. Singapore’s displacement of other landscapes exemplifies sand’s unboundedness and monetary status.

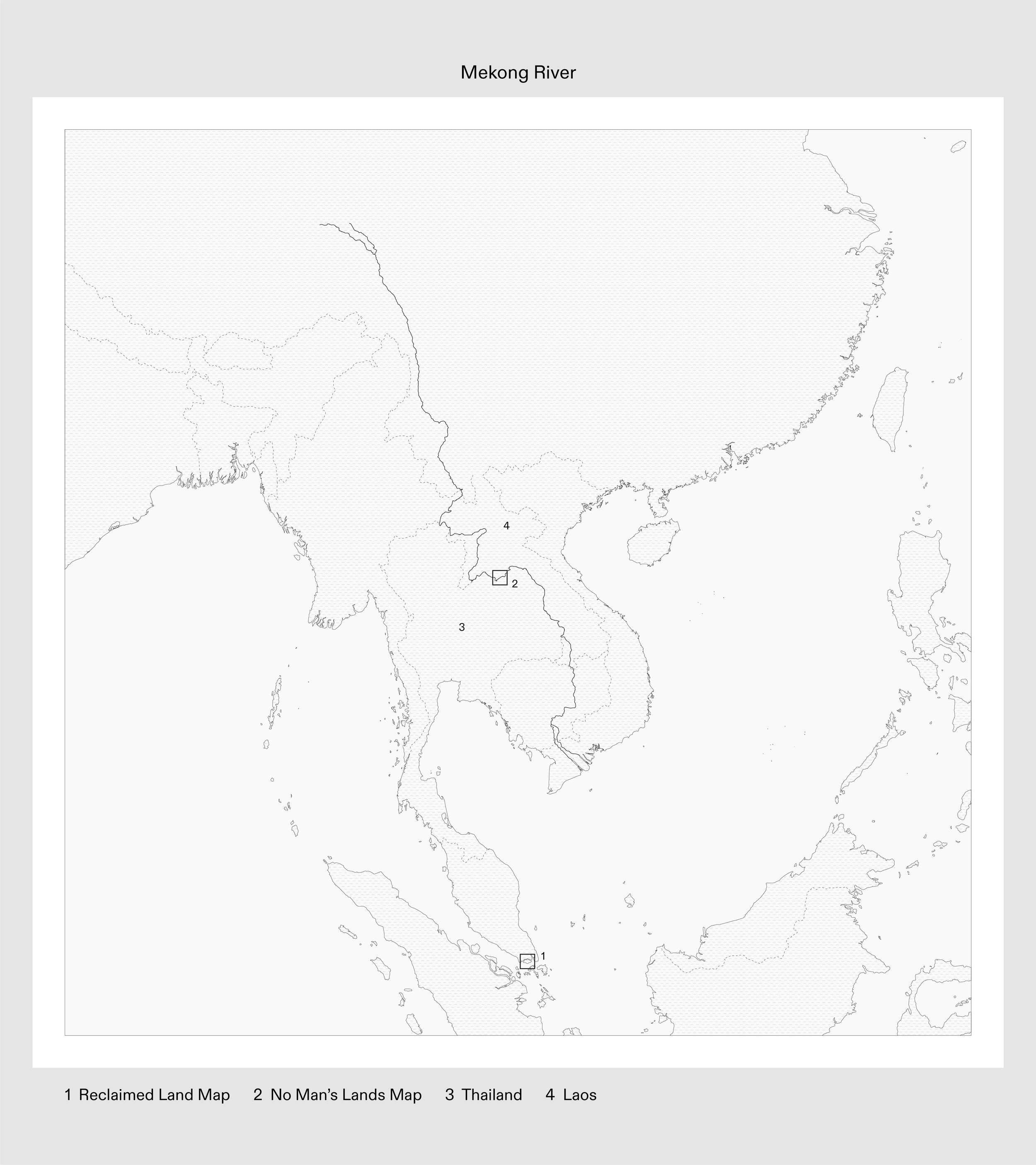

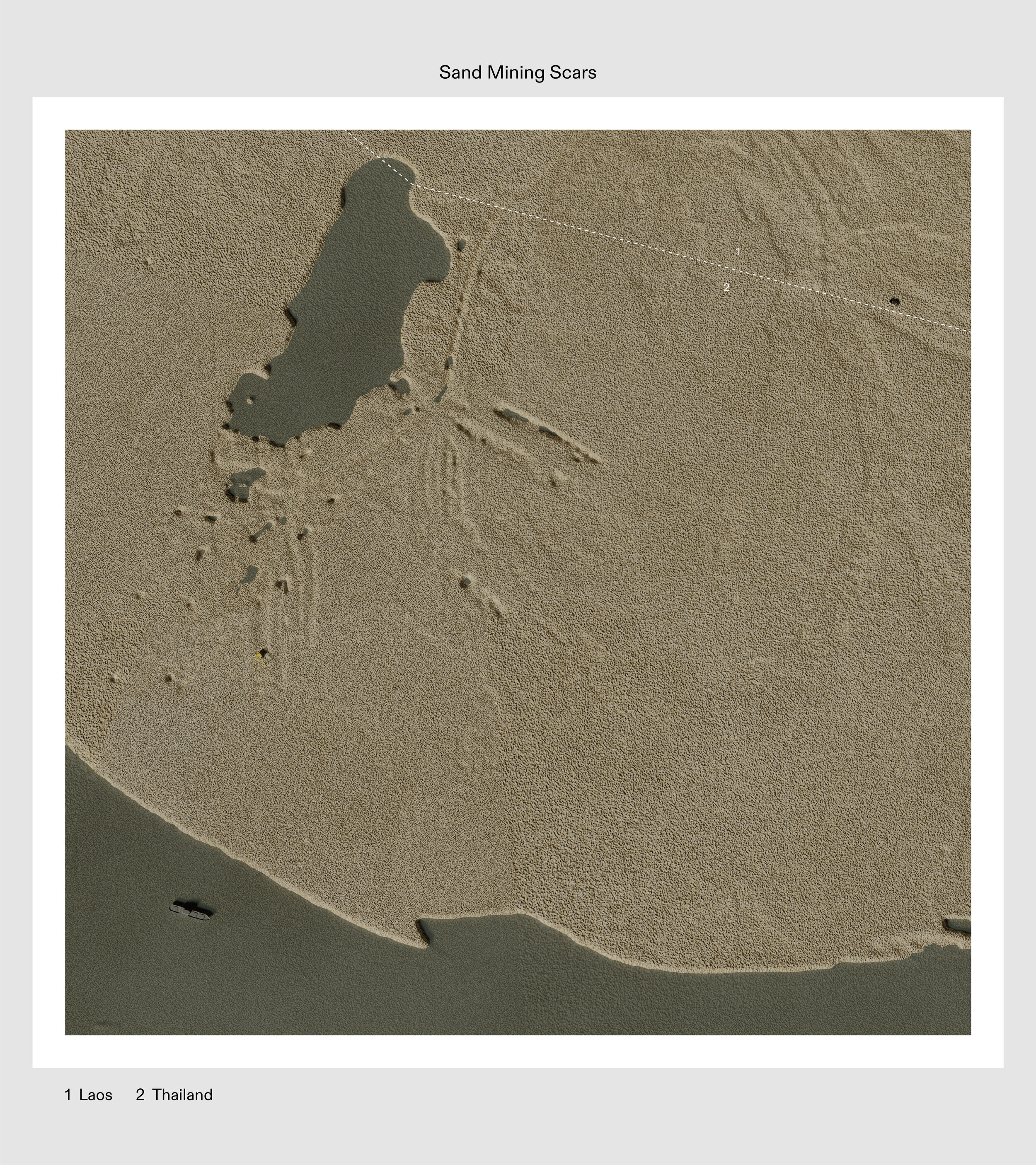

Feeding Singapore’s land reclamation projects, the Mekong River represents the extremes of land as property and resource. Sand is extracted for free to be sold as a commodity, resulting in eroding coastlines and devastation of the river’s biodiversity and water quality. Damming along the border river only exacerbates the sand shortage by interrupting sediment flow upstream.

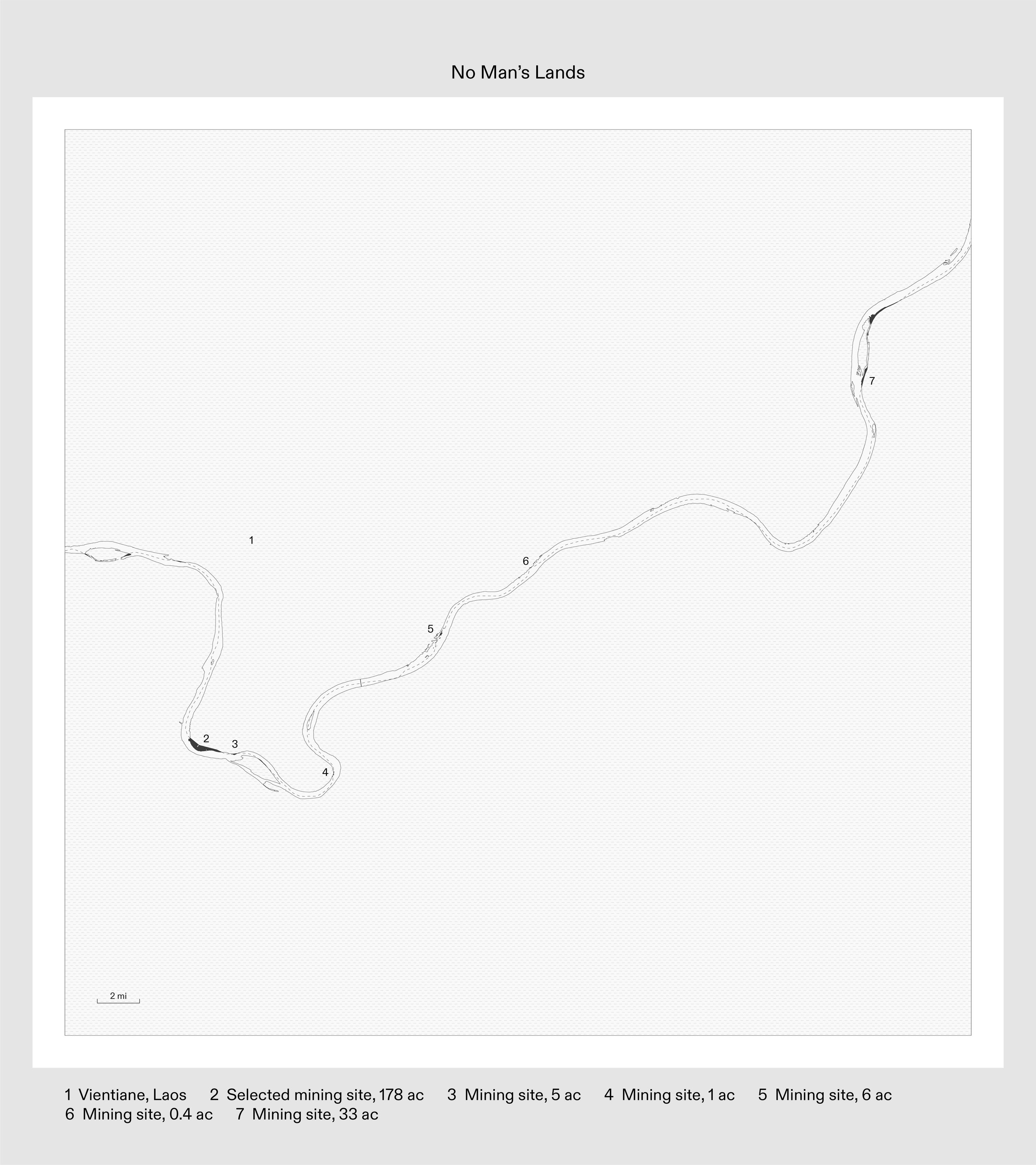

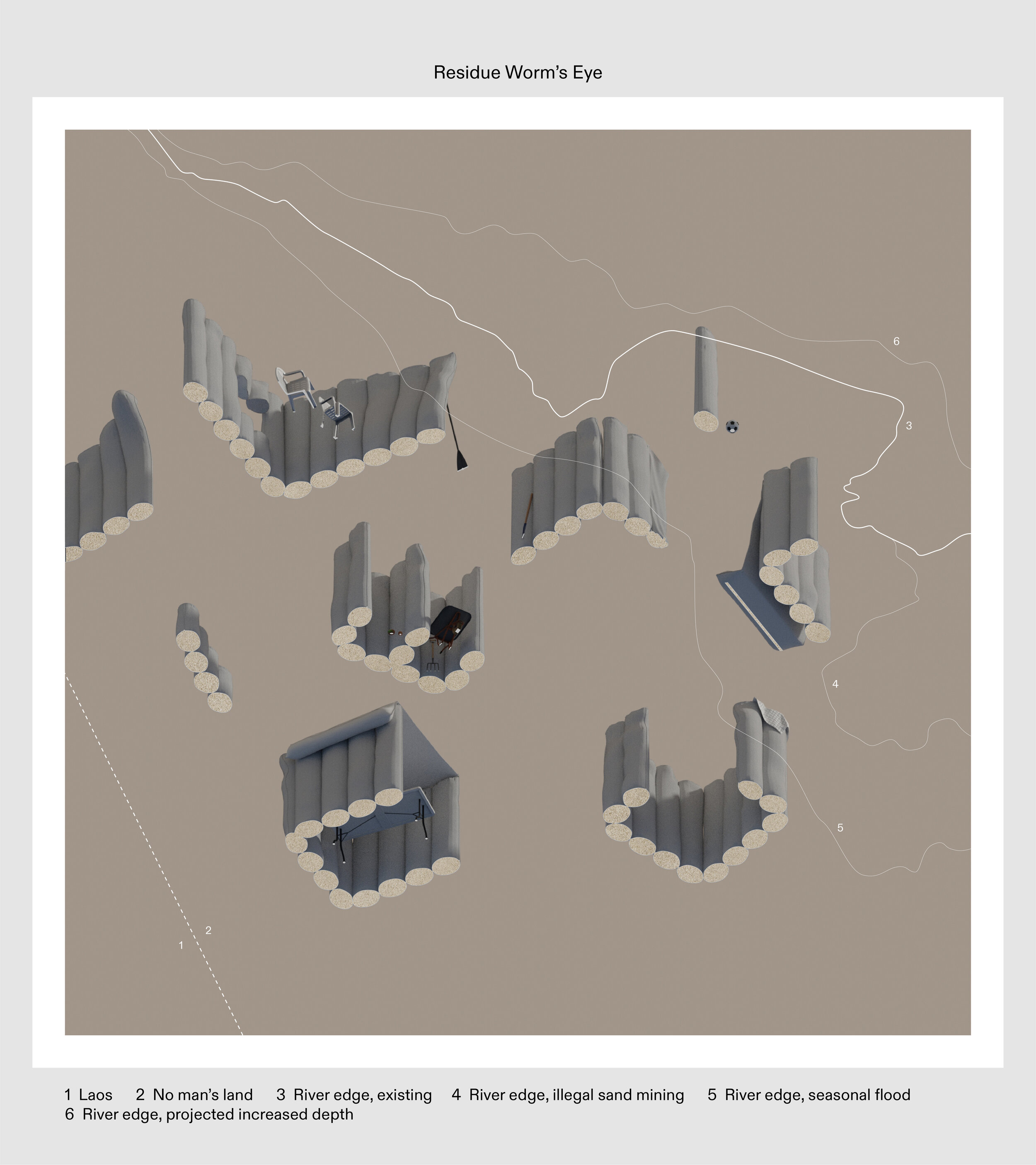

Damming and sand mining have together increased the depth of the Mekong River by over 3 meters in the past 30 years, causing the territorial line between Laos and Thailand, assumed to be fixed along a natural divide, to become misaligned with geography. As the river alters its course and the territorial edge lags in its mutation, gaps, however temporary, reveal themselves in the spaces in between.

The pieces of land trapped between political history and geographic present become islands of ambiguity, or no man’s lands. These sites of territorial confusion present opportunity for architectural agency, identified as potentially productive for disrupting existing sand stories.

This project takes the mining site closest to Vientiane, the capital of Laos, as its place of intervention, but implies a further archipelago of disruptions as other no man’s lands come in and out of focus. This network seeks to irritate capital accumulation by unsettling the politics of mining in contested territories.

However this thesis argues that politics are better understood, and stories are better told, through a more familiar scale of seemingly ordinary moments.

It proposes an alternative to invisible labor and the permanent solidification of material.

It seeks to choreograph other sand stories—ones in which the material is commoned rather than commodified.

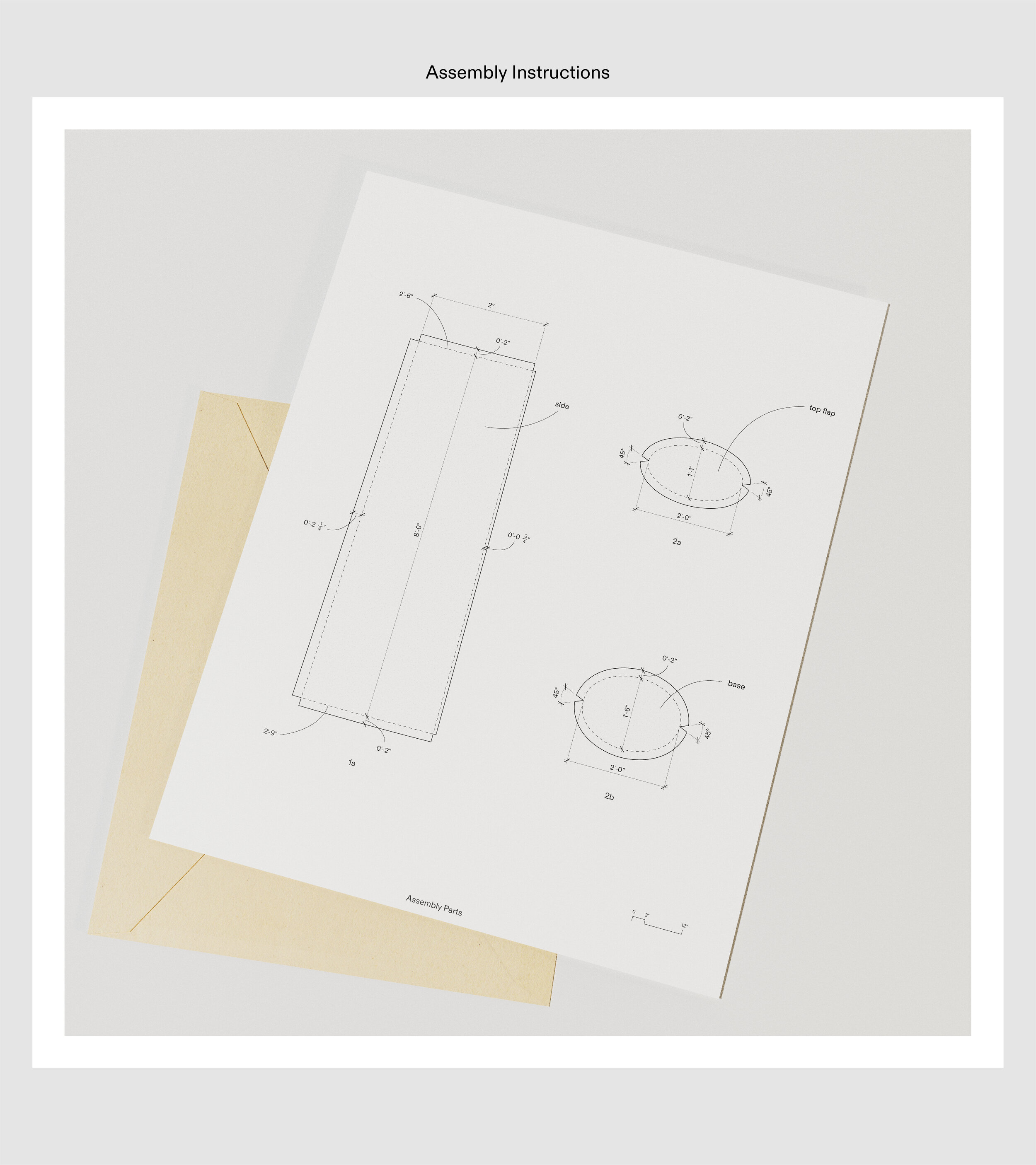

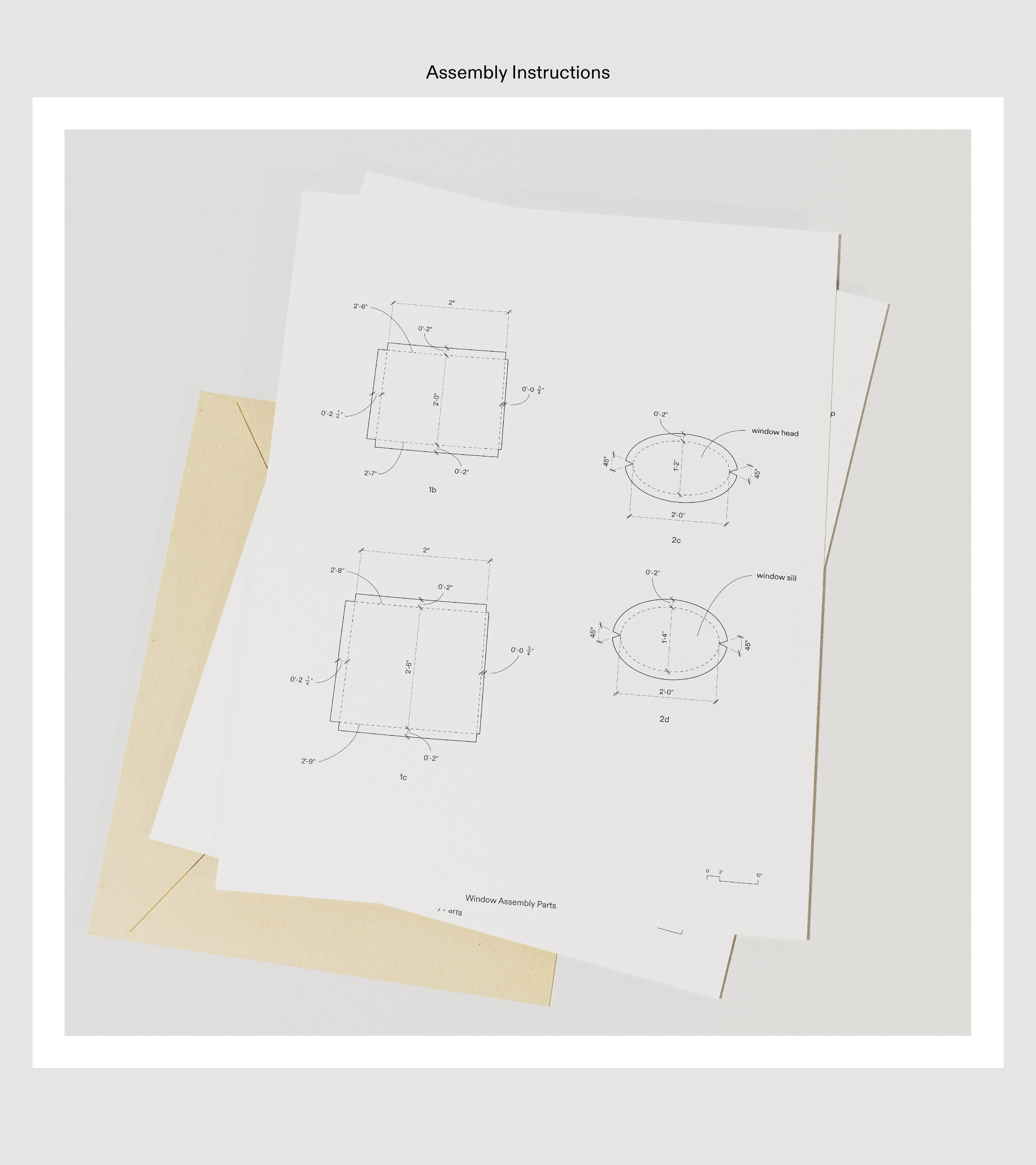

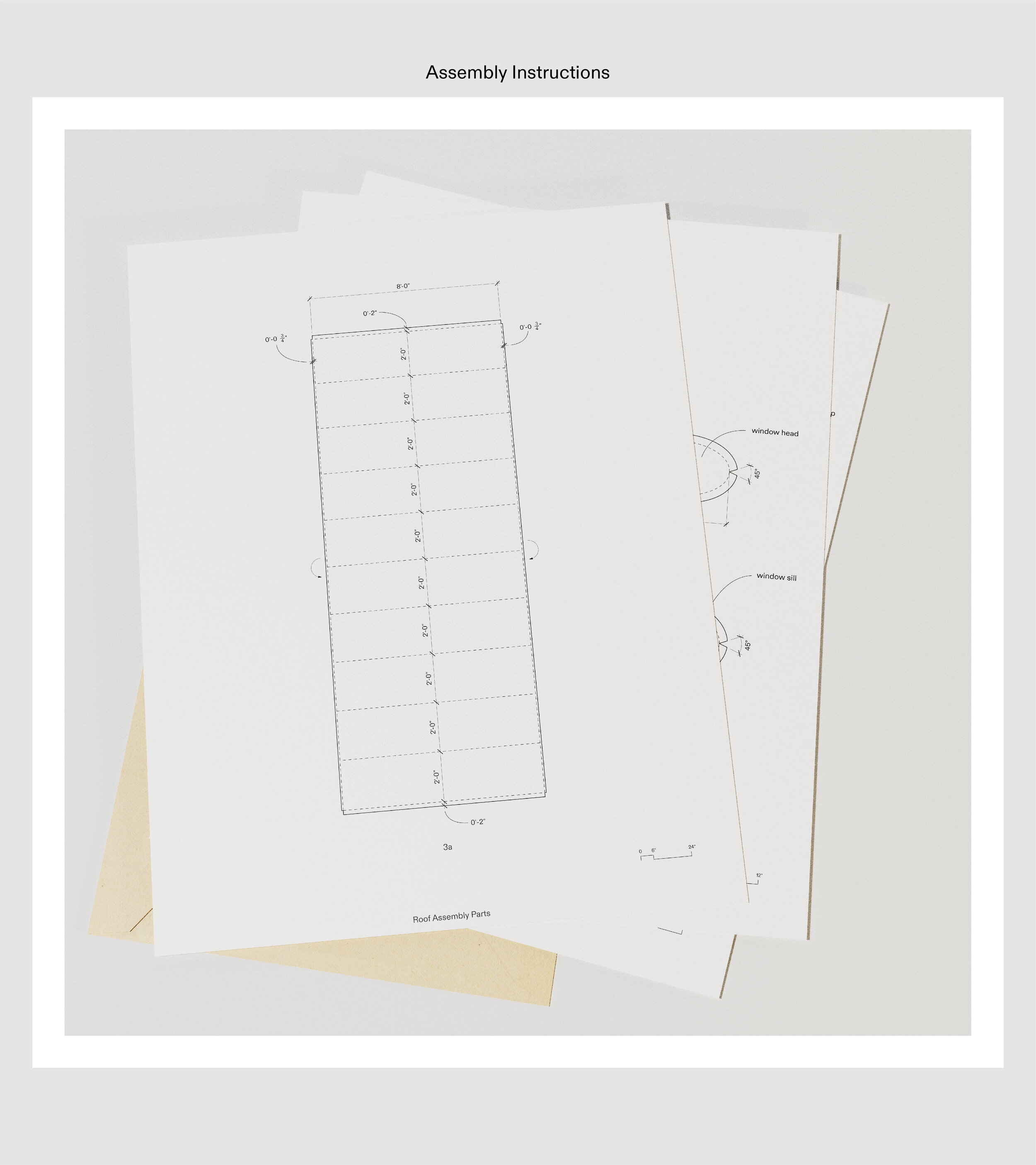

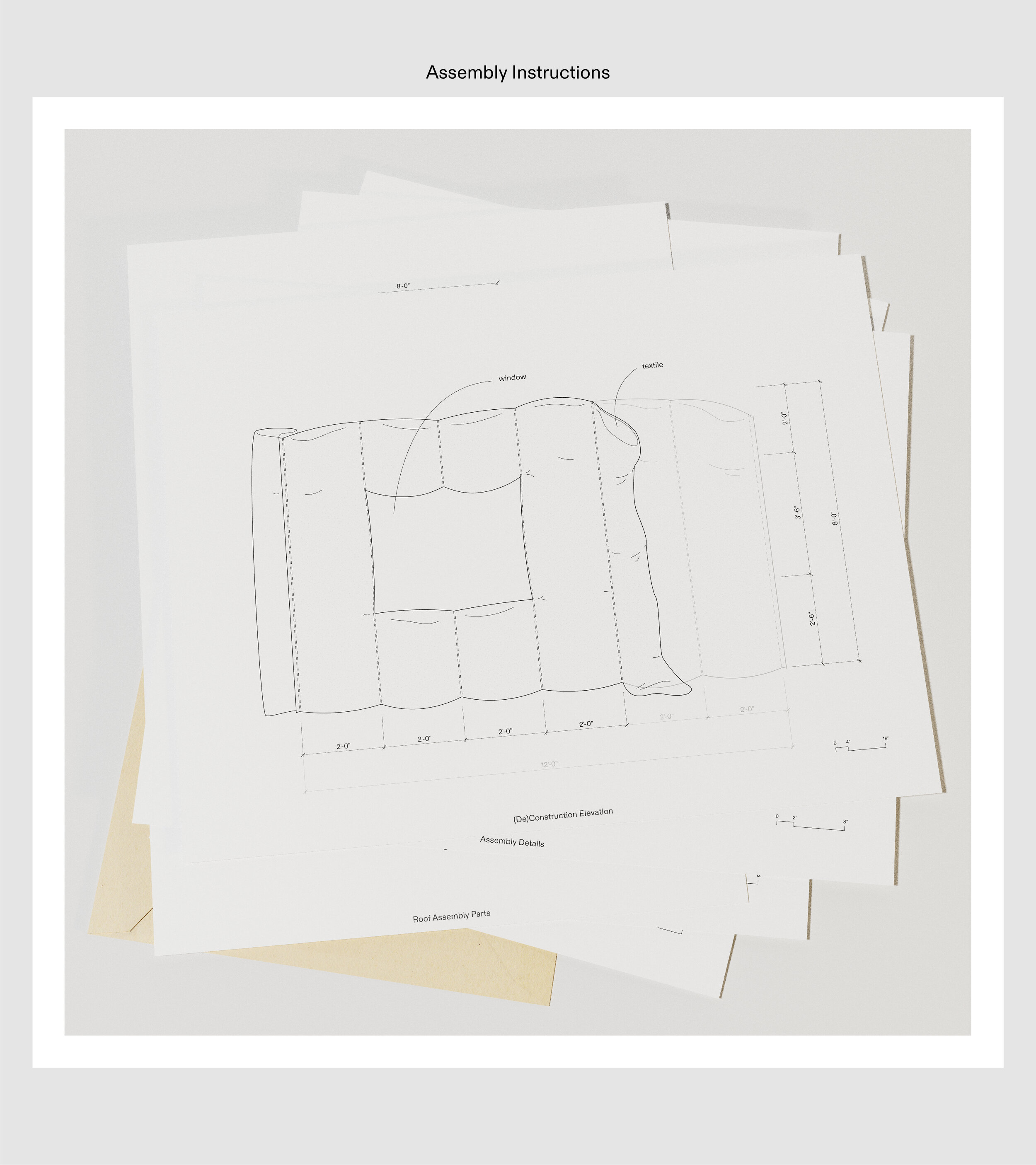

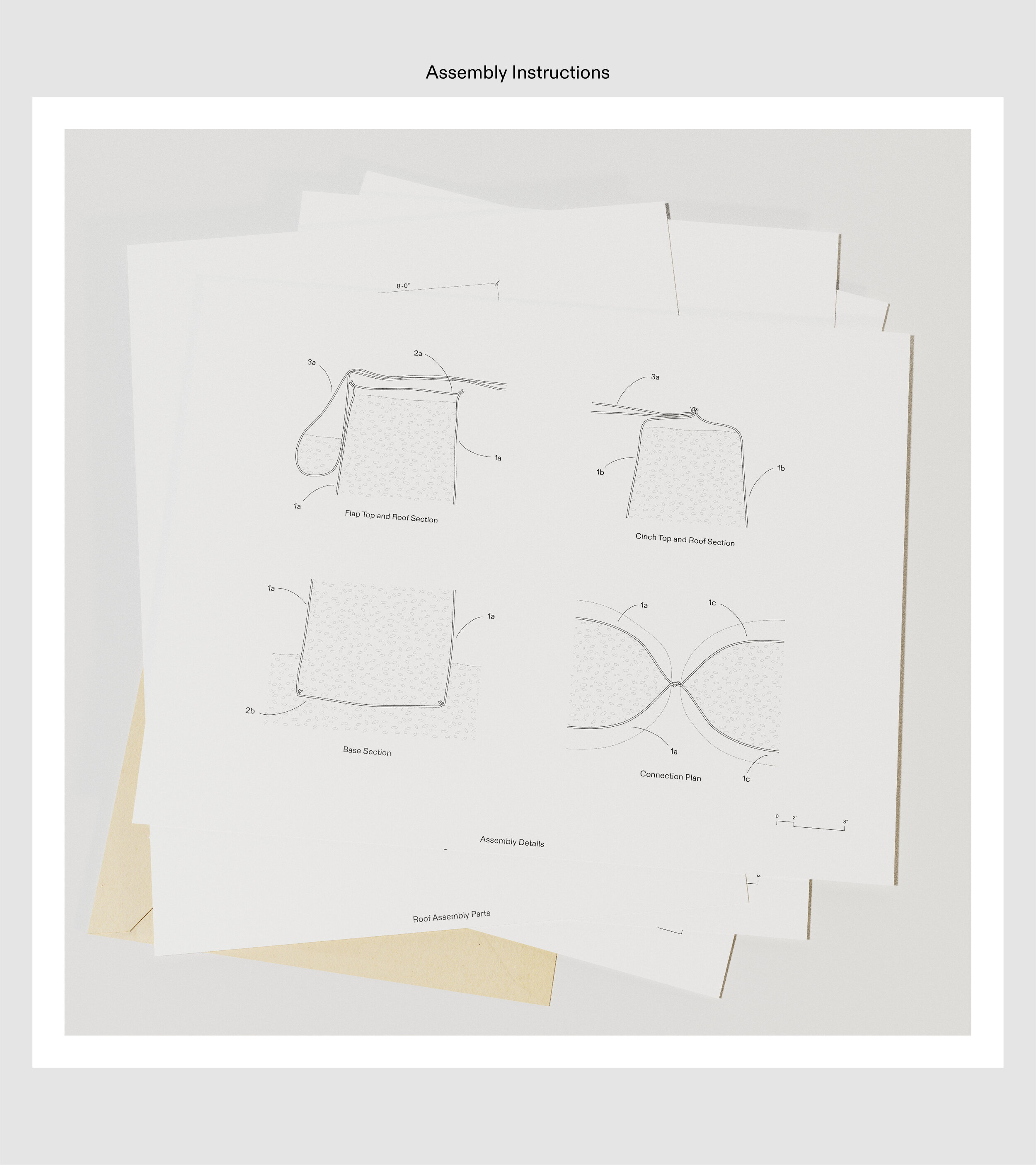

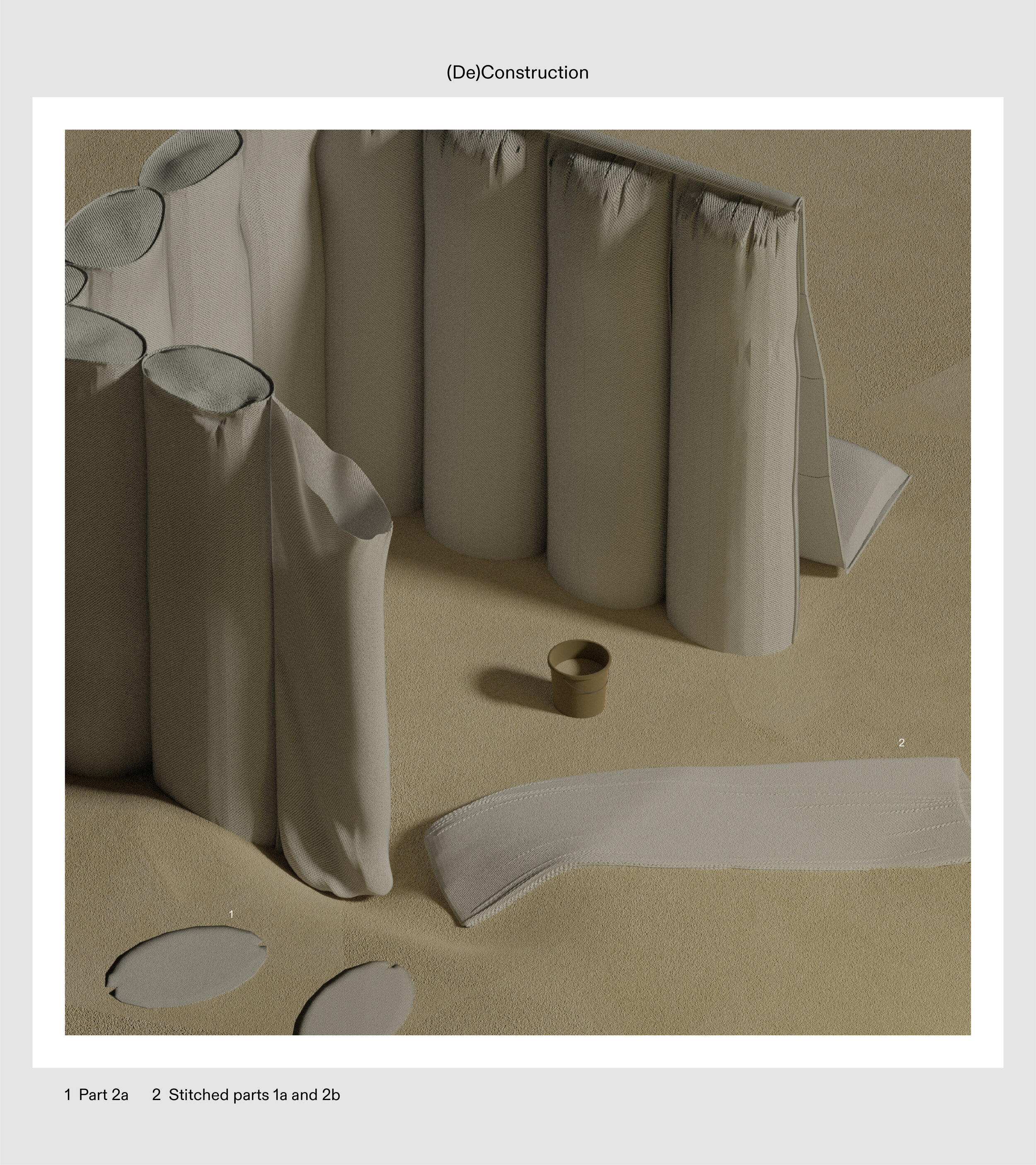

The architect’s role extends beyond identifying sites of opportunity to designing and compiling a set of instructions for appropriation.

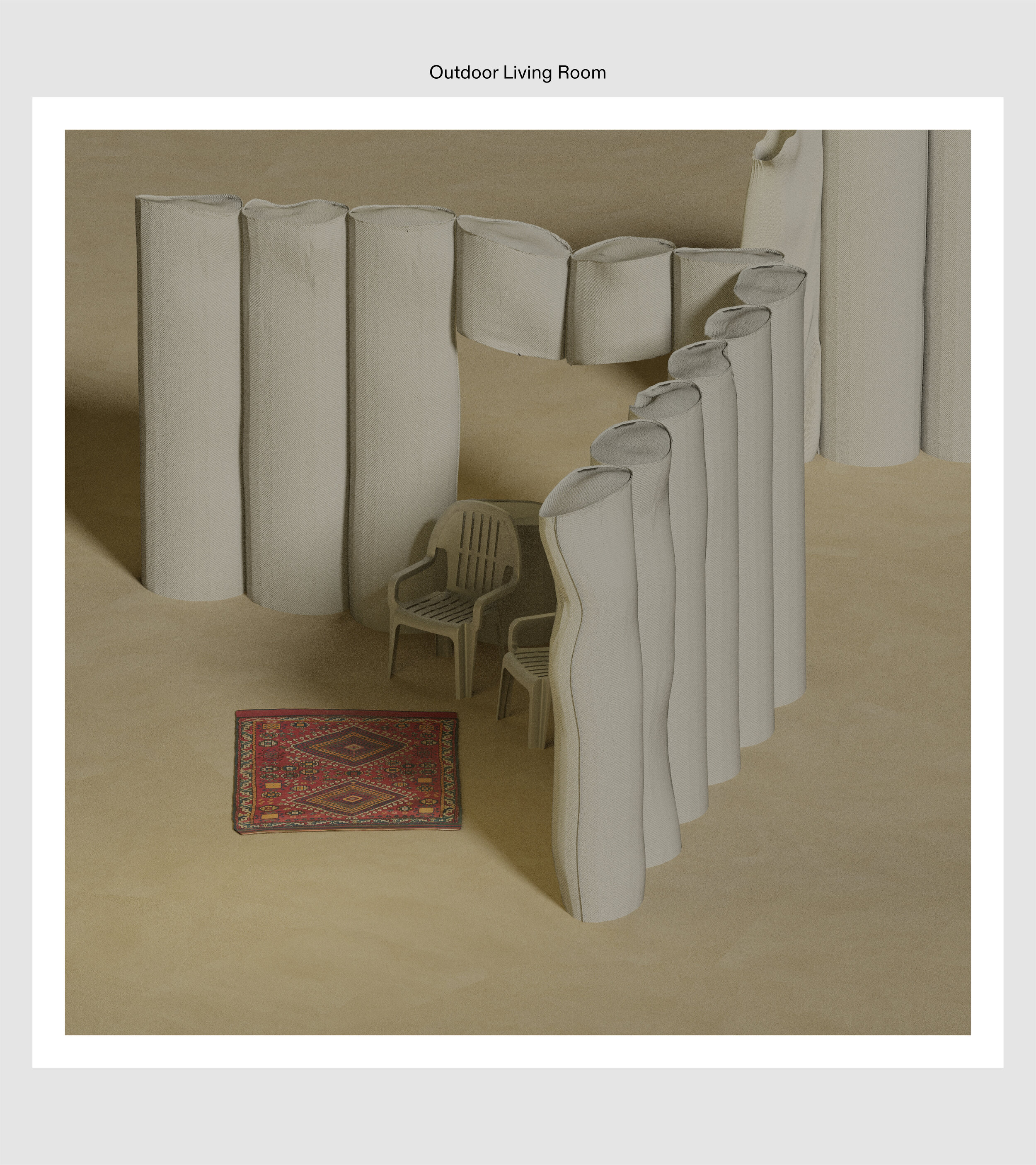

These instructions are provided to the communities surrounding each identified no man’s land, who will act as builders. The manual intentionally leaves room for interpretations and misinterpretations, use and misuse in order to make space for collective decision making and negotiations. A brief material schedule is included in the instructions, attempting to collectivize labor and foster a sense of communal responsibility.

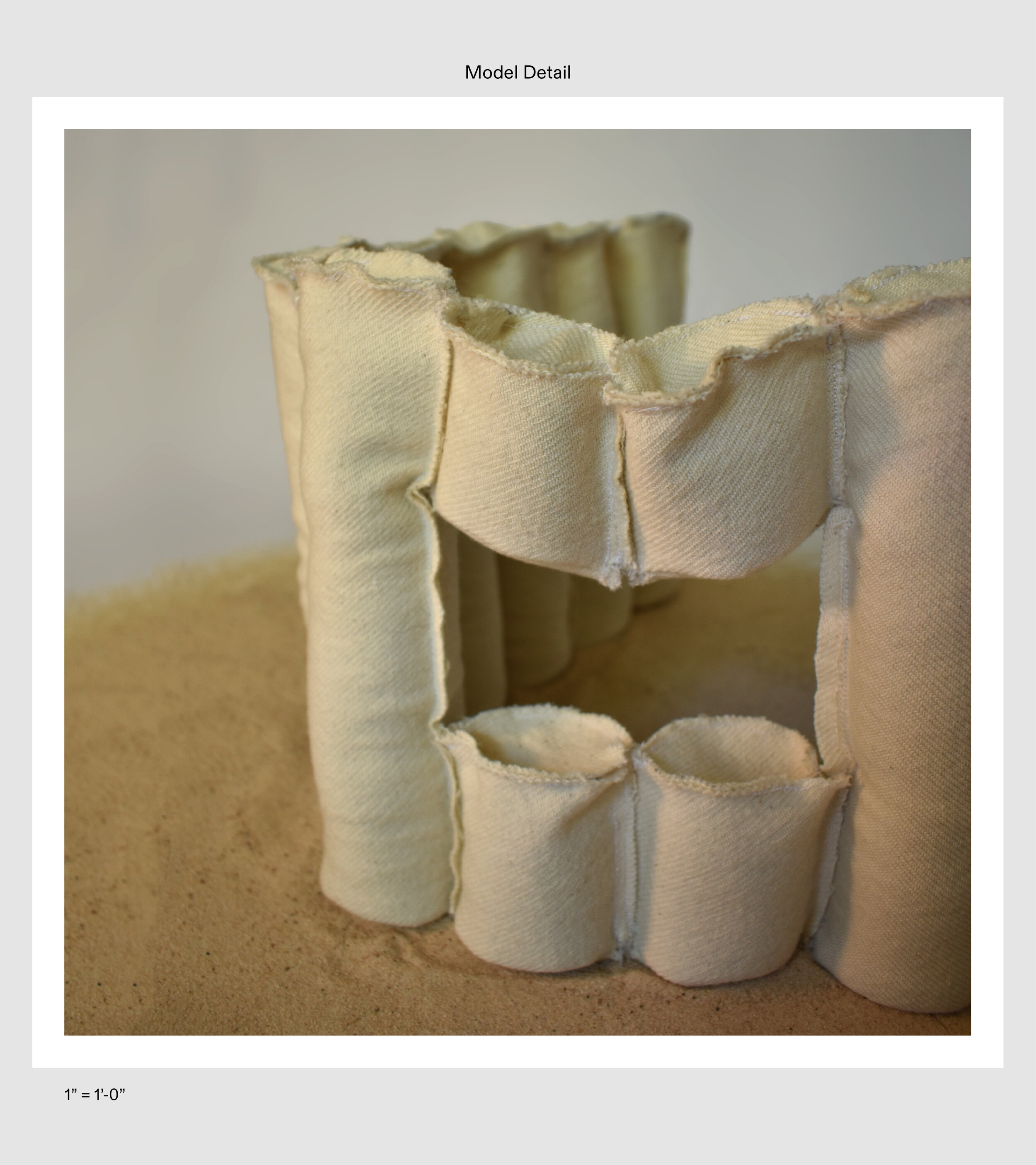

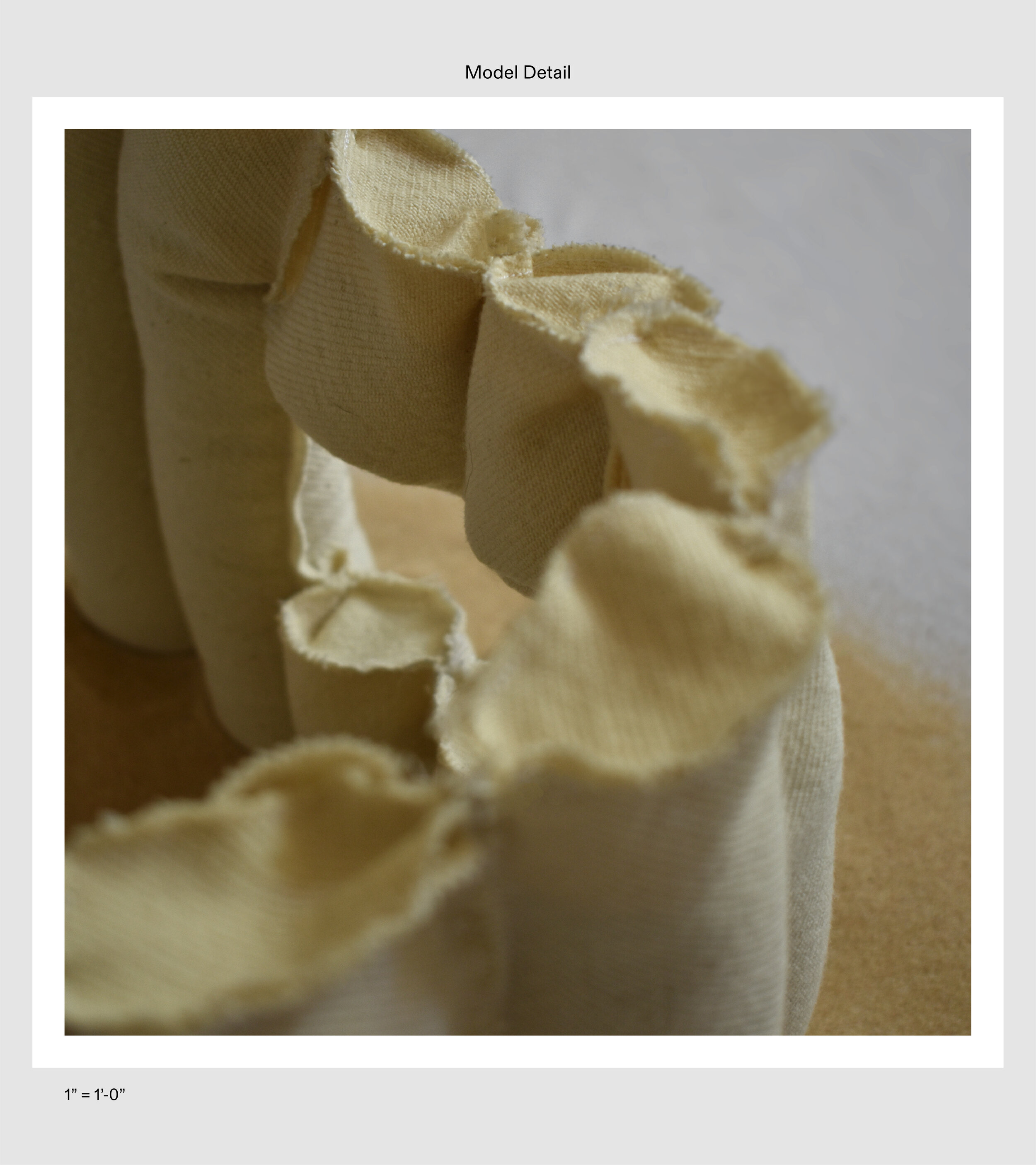

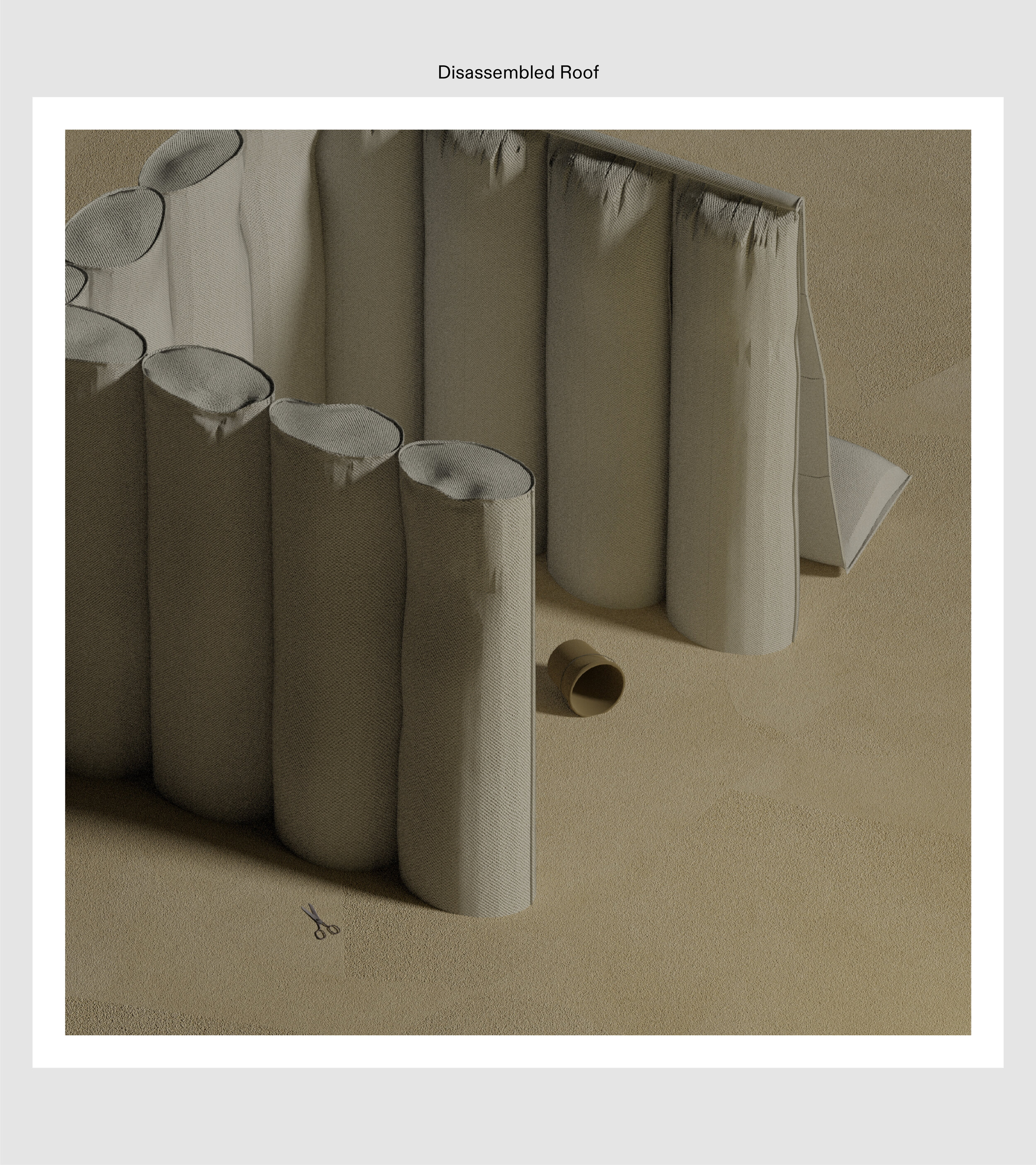

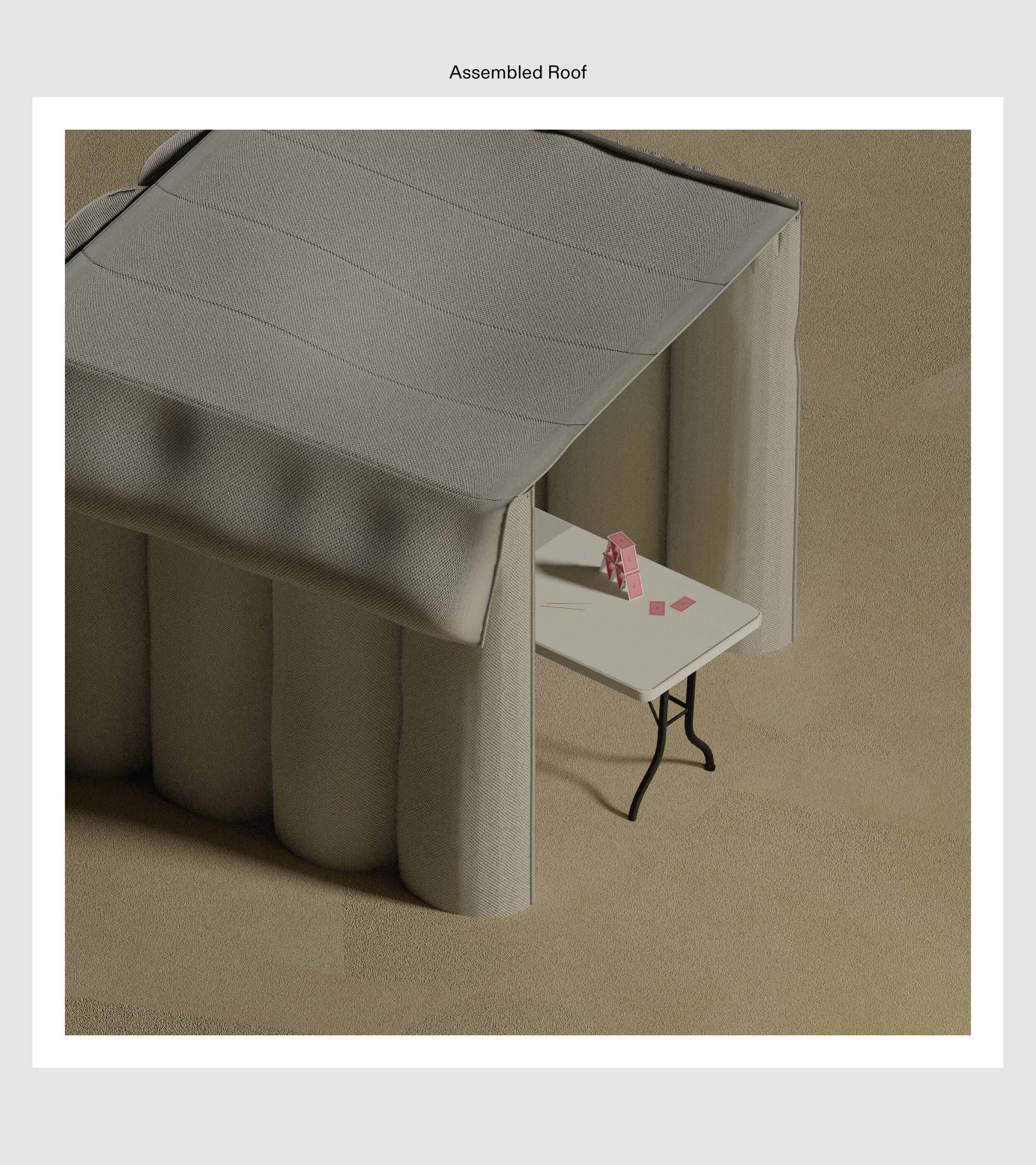

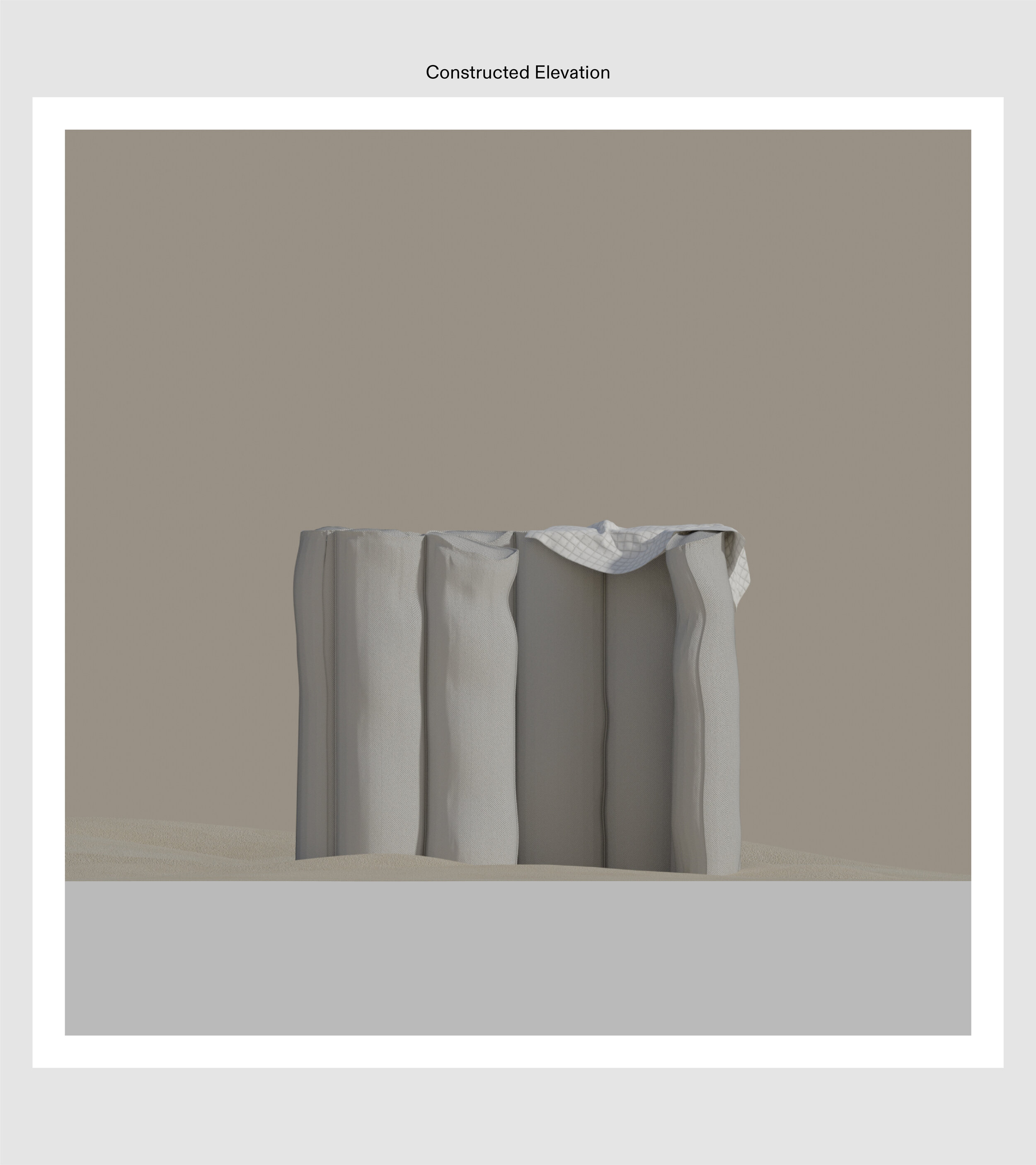

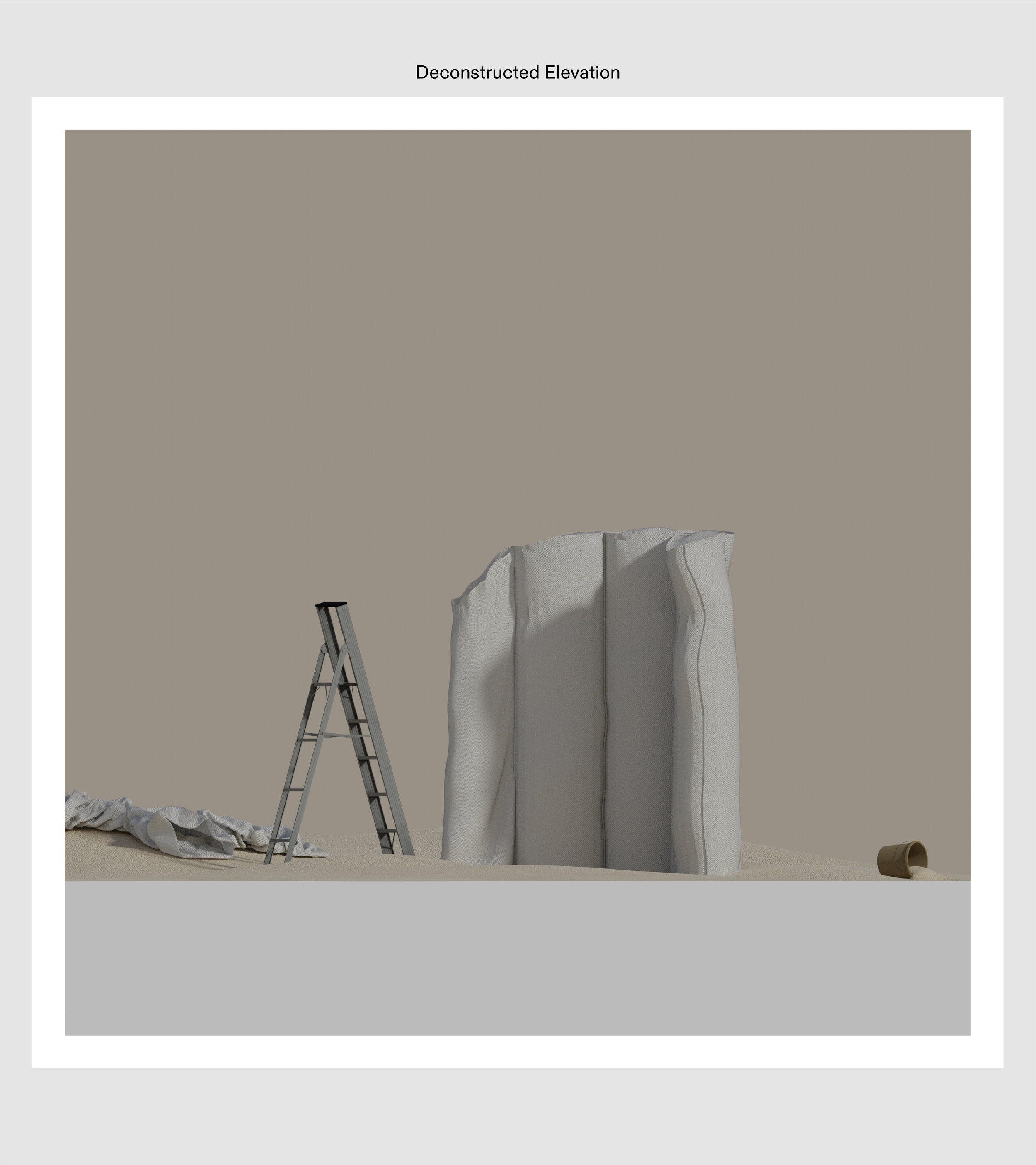

The proposed construction formalizes sand while maintaining the material’s looseness. The architecture is designed to be constantly taken care of and maintained, but also to be deconstructed and released.

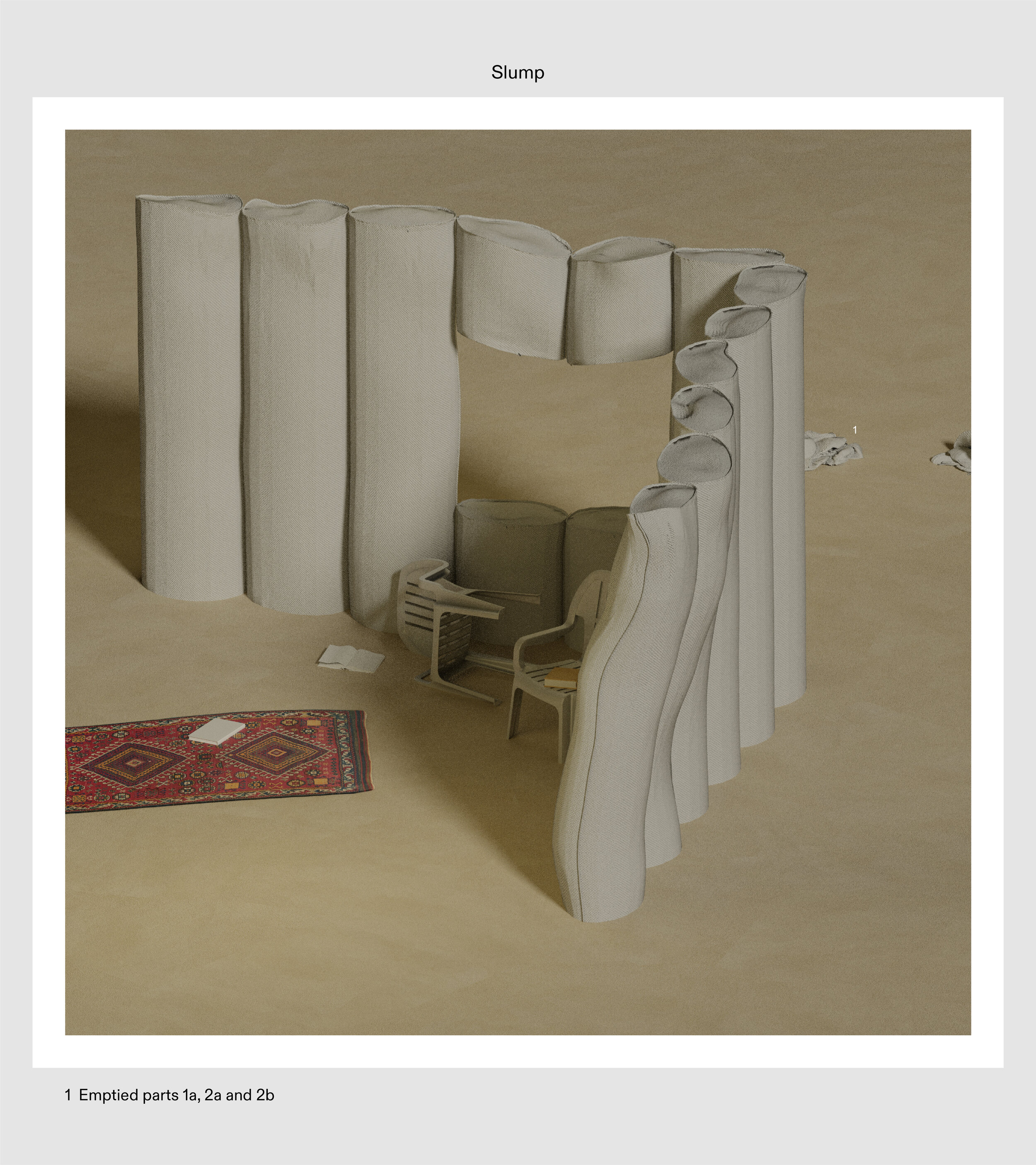

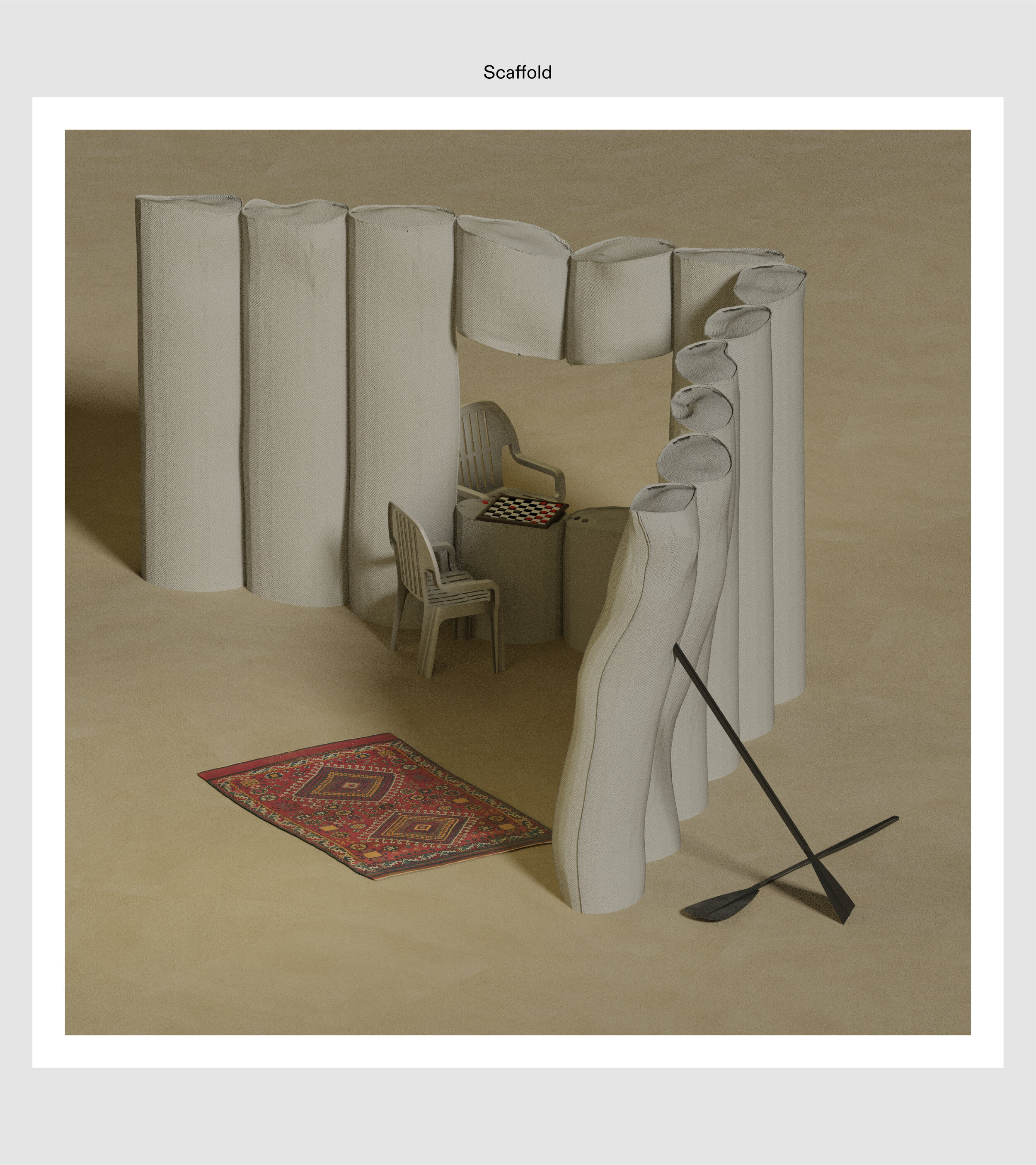

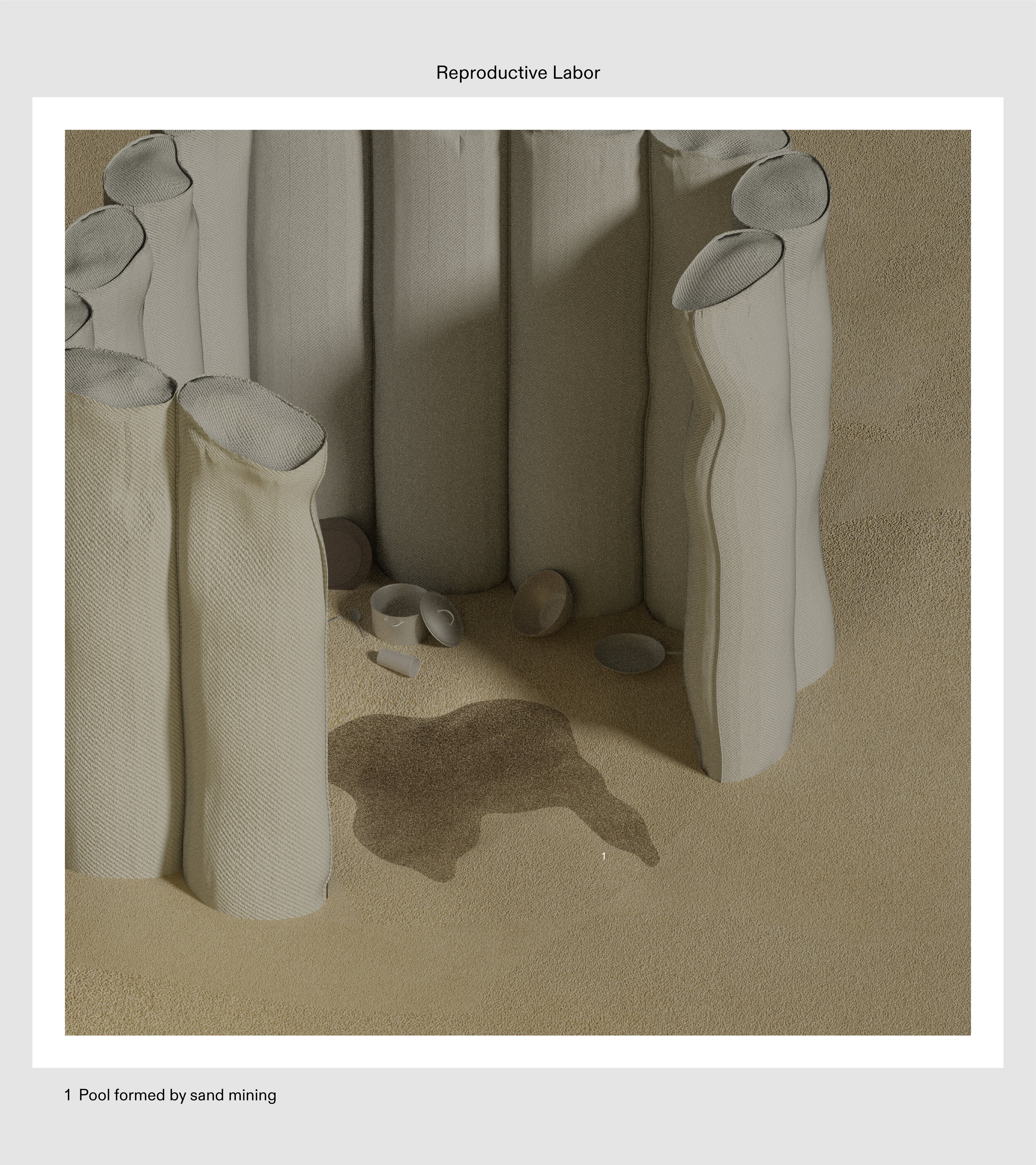

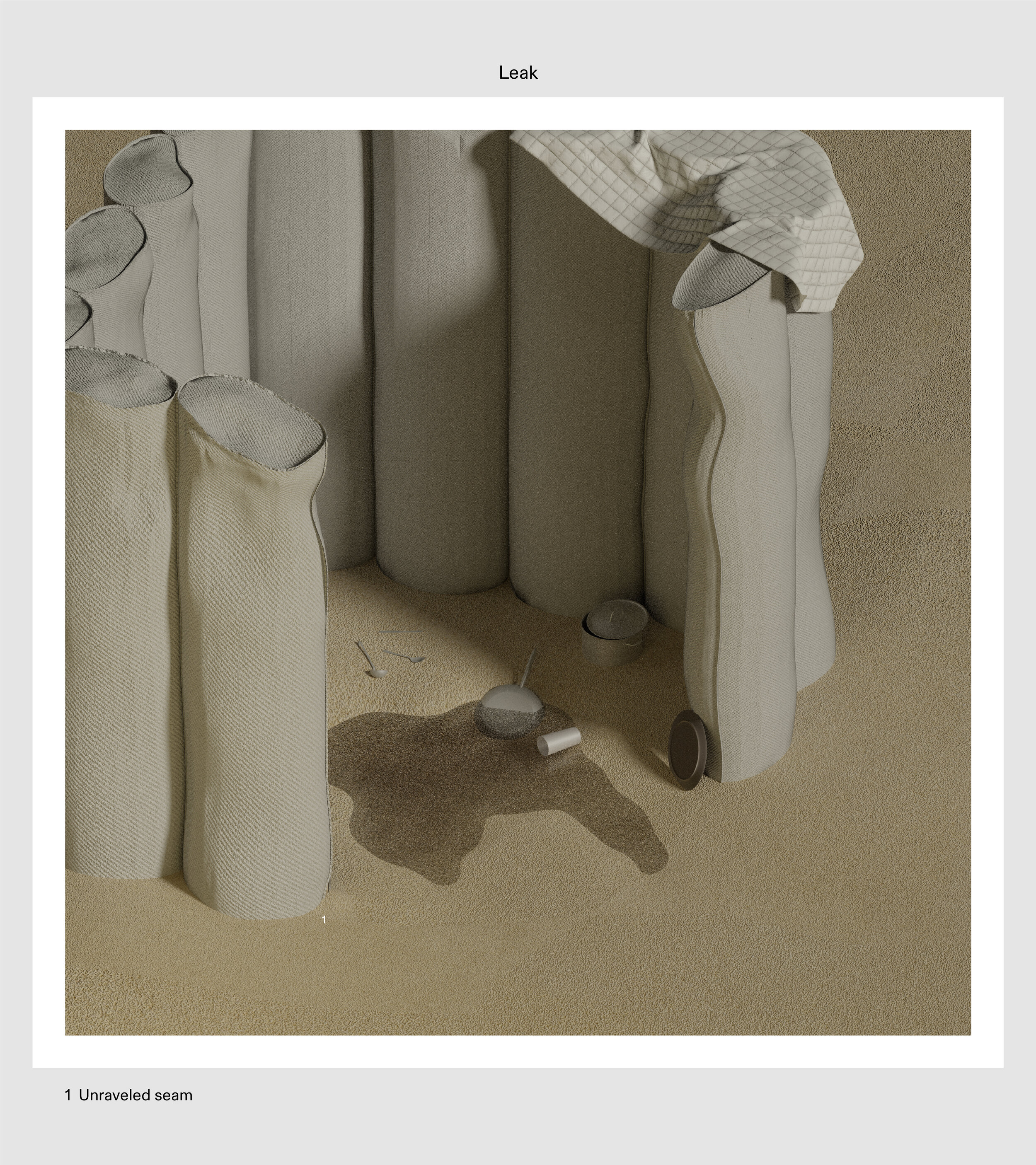

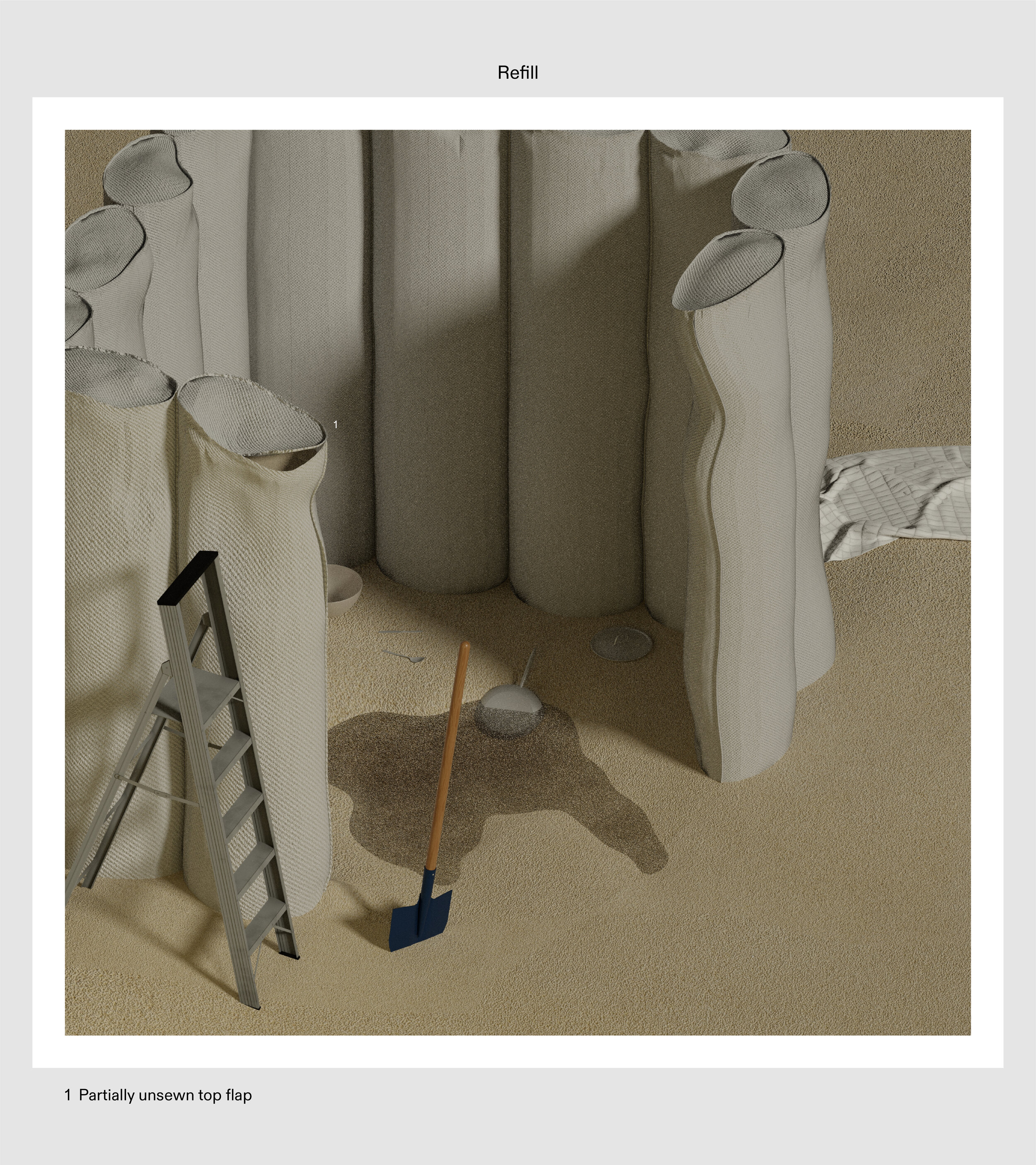

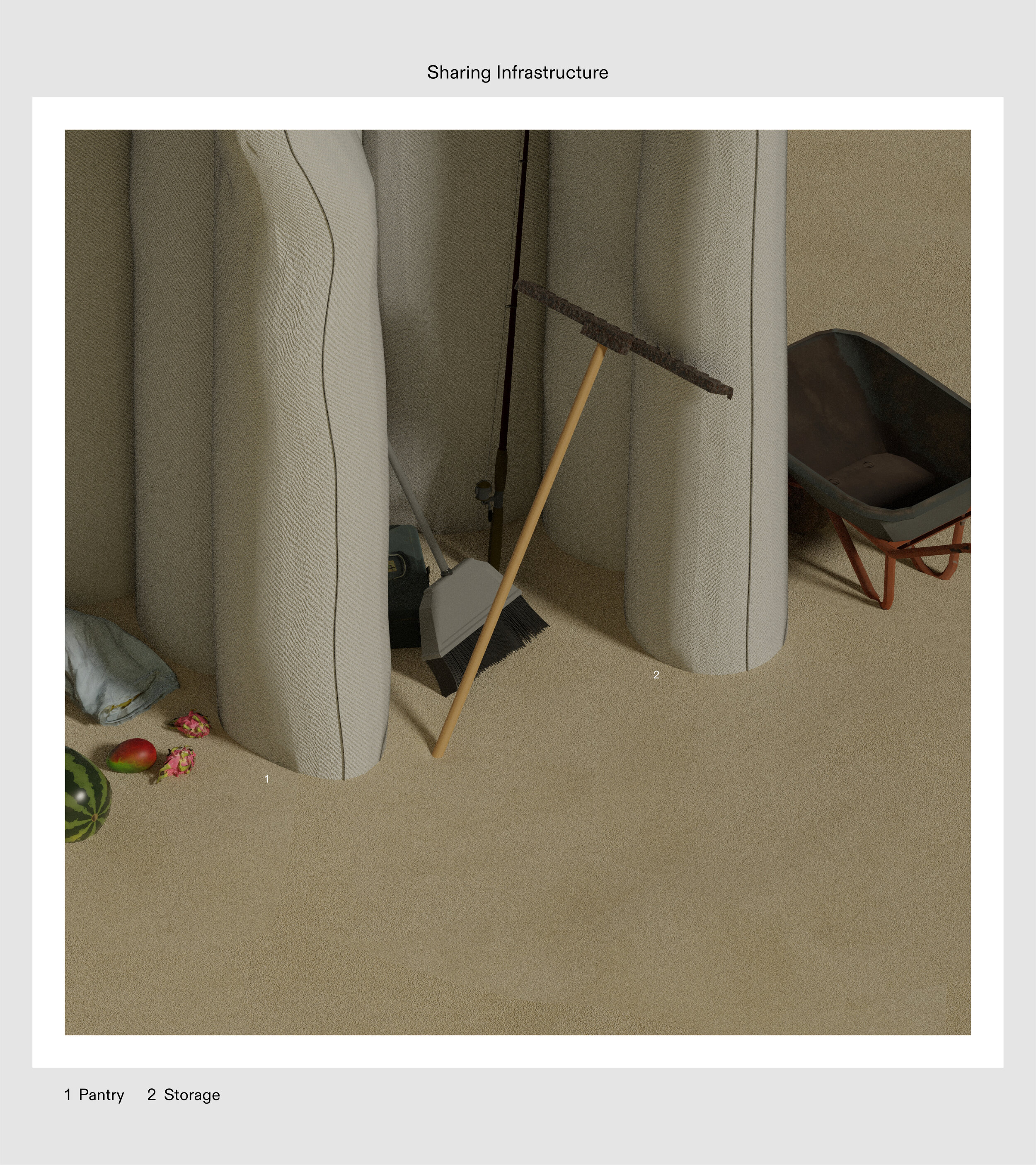

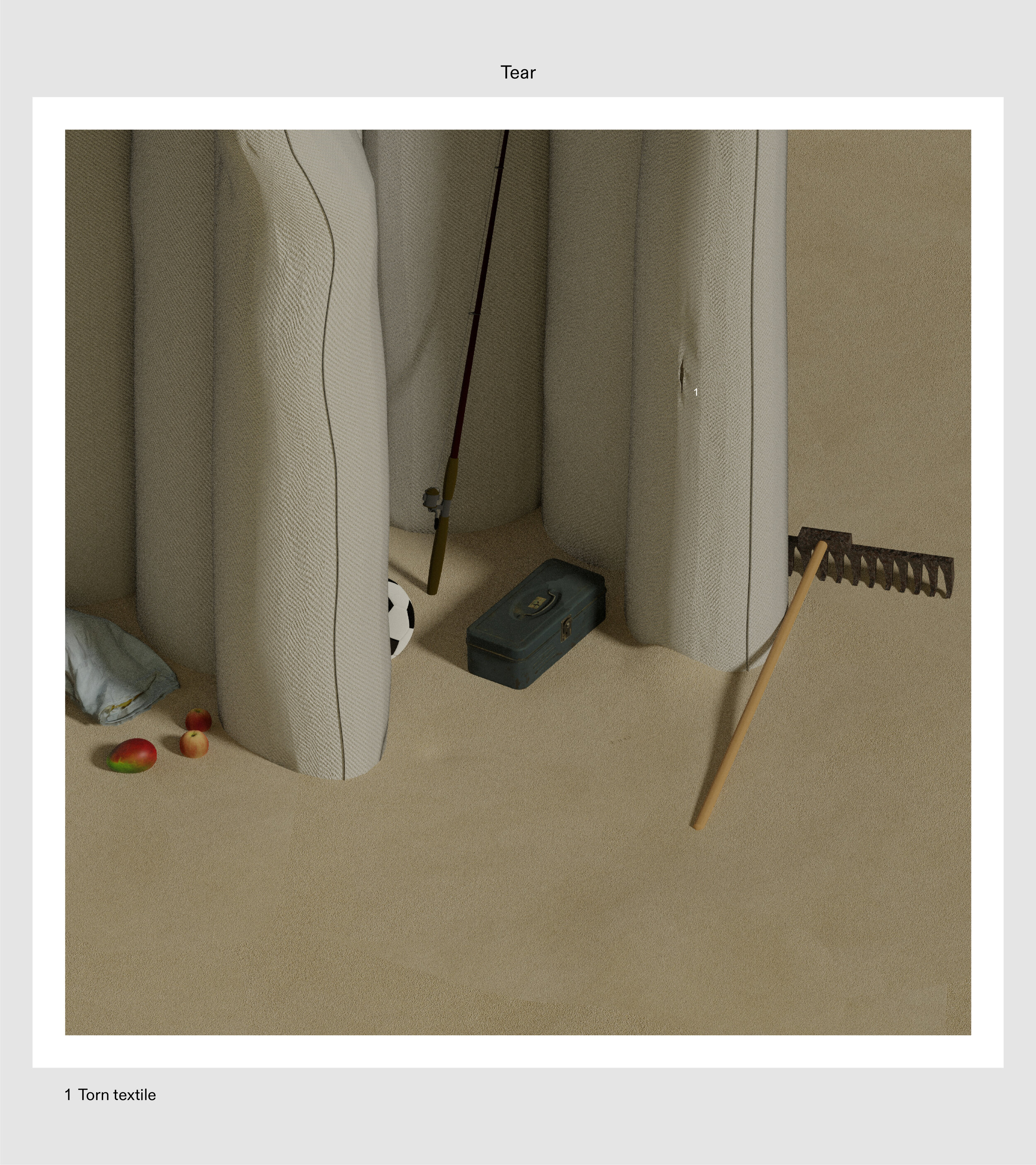

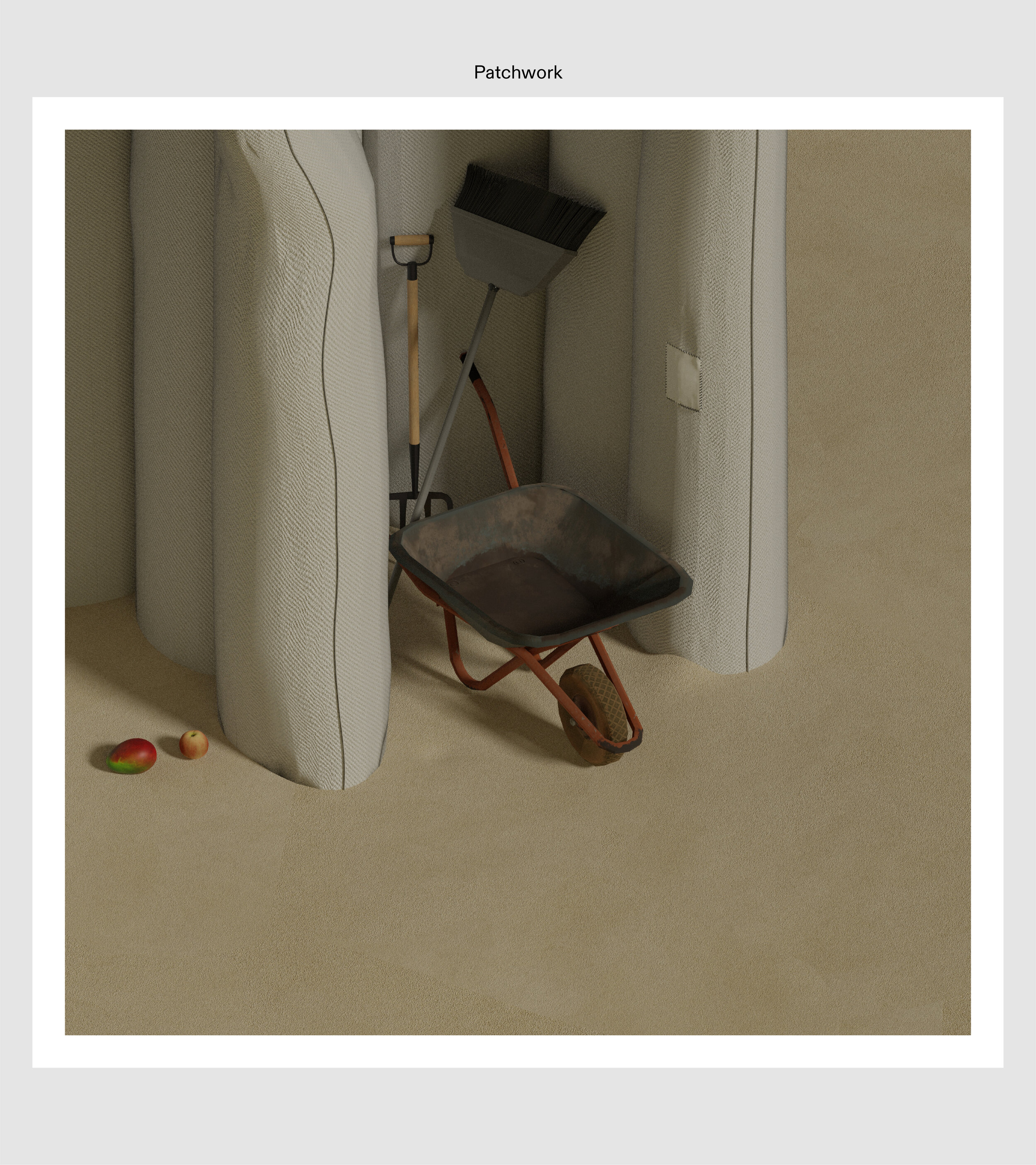

A series of scenarios are depicted to imagine potential use, mistakes and repercussions of the interventions.

Different uses encourage reconfigured forms and varying interpretations and misinterpretations of the instructions. Sand is instrumentalized to render invisible labor visible, from collective construction, repair and deconstruction to the socialization of reproductive care within the spaces. Looseness of material becomes productive not only in maintaining sand’s raw state, but also in making use of its precarity as a building material.

Sand bags inherently droop, flop, sag, slump, necessitating constant making and remaking, repair, and negotiation. This continued maintenance forms structures of care, oppositional to logics of extraction.

Slumping needs a scaffold, leaks necessitate refills, and tears require patchwork.

The constructions together act as a sort of soft infrastructure, supporting commoning of land and material through collective use and enabling an aggregation of interpretations for spaces of gathering, working and sharing. This temporary archaeology can be just as easily disassembled, allowing sand to be unseen as a commodity.

From the microscopic to the geographic, sand tells stories. Drooping sand bags that necessitate structures of care are enabled by the same precarity that destabilizes territory. Sand’s commodity status lends it to existing stories of extraction, material displacement and territorial instability, the latter of which can be rendered productive in not only disrupting existing sand stories, but in telling new ones in the process. These other stories suggest how we might otherwise figure our relationships with material and with each other.